Speaking to the Times of Malta on Friday 19th May, Prime Minister Robert Abela said that although the government is ready to consider the introduction of a revolving door policy for ministers as part of broader good governance reforms, doing so would create an additional burden on the country’s finances.

Abela claimed that ministers who are prevented from taking on a particular private sector role due to a revolving door policy would have to be compensated by the taxpayer.

A revolving door policy forbids public officials from taking up certain roles within the private sector for a period of time after they have left public office, often referred to as a cooling-off period, particularly if they were previously responsible for regulating or legislating the sector.

The intention of revolving door policies is to prevent former public officials from unfairly profiting from their inside knowledge of the sector, to avoid the perception of impropriety or conflict of interest and to minimise the risk of corruption and trading in influence.

It has been widely reported that Cabinet members, as well as several high-ranking public officials, are entitled to a transition allowance to help them transition out of public office, although how this allowance is calculated remains unclear.

Times of Malta received several requests from readers to fact-check whether ministers and Cabinet members who are subject to a revolving door policy would need to be compensated for their cooling-off period.

Does a revolving door policy exist in Malta?

A revolving door policy was introduced for some public employees in 2020, stipulating that employees in posts “that involve regulatory or inspectorate functions” are barred from having a “relationship of profit with a private enterprise or non-government body with which they have dealt during a period of up to five years” in the two years after they have resigned their post.

This same provision is also present within the code of ethics for public employees, set out in the Public Administration Act. A 2019 statement issued by the standards commissioner said that this provision also applies to persons of trust within a minister’s secretariat.

Anybody who breaches the directive may be fined the equivalent of three years’ salary.

The directive also establishes the Revolving Door Policy Governing Board, which is responsible for identifying posts that are subject to the policy, as well as monitoring the policy to ensure that it is being implemented correctly.

The members of the board are appointed by the Prime Minister, however, its current members are not listed on the government’s website. Questions sent to the head of the civil service, Tony Sultana, about who sits on this board remain unanswered at the time of publication.

The directive lists several roles across various public bodies that would fall under the scope of this policy. However, the policy does not currently apply to elected officials such as the Prime Minister, members of Cabinet or MPs.

Are these public officials compensated?

No, the directive which established the policy does not indicate that public officials who are subject to a cooling-off period are entitled to any financial compensation.

This was confirmed by well-informed sources who told Times of Malta that no compensation is awarded to public officials in cases where they must serve a cooling-off period.

How do revolving door policies work elsewhere?

An analysis carried out by Transparency International found that while approaches to the issue differ across countries, measures “usually include the adoption of cooling-off periods, the establishment of advice bodies, as well as the adoption of proportionate and dissuasive sanctions for both public individuals and companies not complying with the law”.

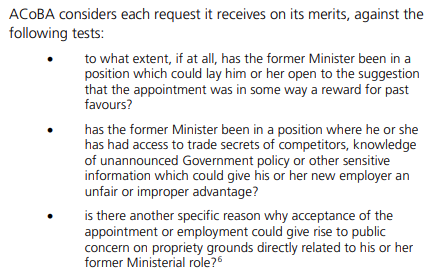

One example is that of the UK, where ministers and top public officials are subject to regulations set out in the Business Appointment Rules and the Ministerial Code when leaving office.

These rules say that former ministers are not allowed to lobby the government for a period of two years after their resignation and must seek advice from the Advisory Committee on Business Appointments (ACoBA) over any paid or unpaid roles they would like to take up throughout this period. The committee then publishes the advice it provides for each request on its website.

Do other countries compensate top elected officials?

An analysis carried out by the OECD in 2015 found that the length and nature of the cooling-off period tended to vary across countries, often depending on the seniority of the post. Financial compensation also varied, with many countries not providing any financial compensation at all.

The analysis found that among the 36 countries under the spotlight, 18 of them had a cooling-off period in place for ministers or members of Cabinet. Of these, only four involved some degree of financial compensation.

Likewise, 14 countries introduced a cooling-off period for Prime Ministers, with only three (Austria, Norway and Spain) providing financial compensation for this period.

Nine countries had a cooling-off period for Presidents, however only two offered some form of financial compensation.

Verdict

Although it is within the rights of the state to provide financial compensation for elected officials who are serving a cooling-off period, this is not obligatory and is at the discretion of the government of the day.

Research carried out by independent international organisations found that of the countries that have established a cooling-off period for high-ranking elected officials, a relative minority have opted to provide financial compensation.

Furthermore, the revolving door policy for public employees introduced in 2020 does not entitle employees to compensation for serving a cooling-off period.

The claim is therefore false as the evidence clearly refutes it.

The Times of Malta fact-checking service forms part of the Mediterranean Digital Media Observatory (MedDMO) and the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), an independent observatory with hubs across all 27 EU member states that is funded by the EU’s Digital Europe programme. Fact-checks are based on our code of principles.

Let us know what you would like us to fact-check, understand our ratings system or see our answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the service.