Whether or not you watched the Paris Olympics opening ceremony last week, you undoubtedly know about the controversy made out of one particular moment.

People the world over have described the act as a ‘mockery’ of Christianity. But there is more to the picture than meets the eye.

The segment in question was ‘Festivité’. A woman in blue with a halo-like headdress stood at the centre of what appeared to be a long table, flanked by other flamboyantly-garbed performers, including drag queens (see from the 1:55:04 mark in this video).

Were they at a table? Maybe, maybe not. It was bare of plates and goblets, and with good reason – it acted as a catwalk for models forming part of a fashion vignette in the ceremony. Later on, a giant silver plate was placed on the platform; its giant opaque cloche was lifted, revealing a blue-painted man sporting a sash made of flowers and lying in a bed of rainbow-hued foliage. He burst into song as the other performers danced behind him.

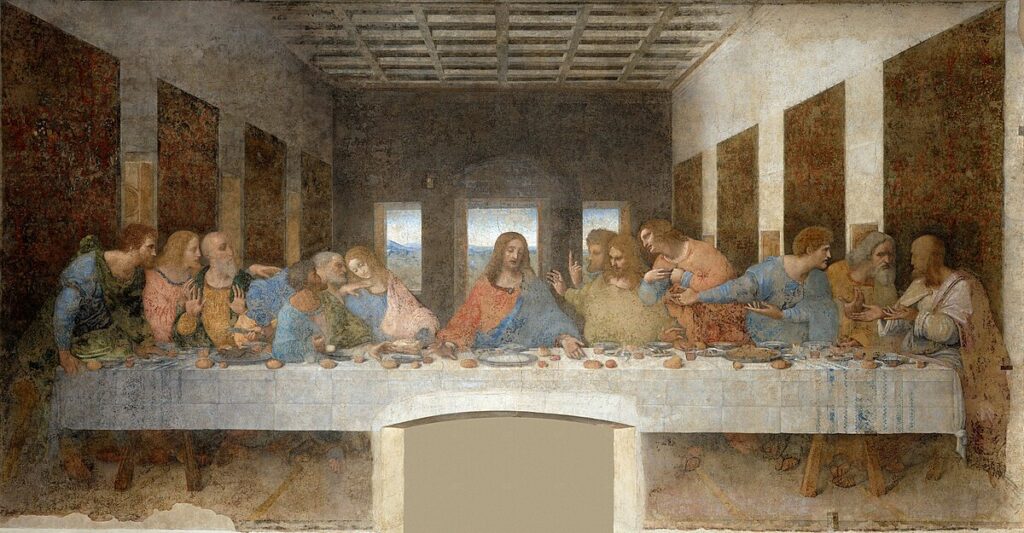

Images of the scene went viral. The act, people said, was an insult to Christians. Church leaders and politicians from around the world weighed in. Many seem to believe that ‘Festivité’ was a biblical parody inspired by Leonardo Da Vinci’s ‘The Last Supper’.

Leonardo Da Vinci’s The Last Supper (from Wikimedia Commons).

And that is just the point: many seem to believe that the segment was a biblical parody inspired by Leonardo Da Vinci’s ‘The Last Supper’, so it must be the case. Mustn’t it?

Whether or not the segment was actually a depiction of the biblical scene is a different matter entirely.

The point here is that the narrative spread rapidly and widely, despite the segment bearing very little resemblance to the Christian scene depicted in Da Vinci’s work. For one thing, central to the Last Supper are the twelve apostles. In Paris, far more than twelve people lined the platform.

Then there is the matter of physical framing. Da Vinci’s painting fixed in our cultural imagination a particular perspective of Jesus’ final meal with his apostles: all figures in his painting sit at the same side of the table, so the scene has an almost theatrical quality to it. The portrayal follows a golden rule of traditional performance art and filmmaking: it doesn’t break the fourth wall, that imaginary boundary between audience and performers. The Paris’ ‘Festivité’ segment broke this convention. The camera was not stagnant; it shifted focus, changing angle completely as models strutted down the length of the catwalk, revealing more dramatically-dressed revellers on the opposite side of the platform as it did so (see from the 1:55:35 mark in this video).

But on social media, people grabbed onto the single shot that in framing alone perhaps somewhat resembled Da Vinci’s work.

Again, the point here is not whether ‘Festivité’ really was inspired by the biblical story. What we are interested in is the fact that the condemnation seems to be based on a single image alone, cutting out the bigger picture – because this is exactly how (mis)information spreads so efficiently and effectively. When things like religion and LGBTQ+ issues – which tend to spark a particularly strong emotional response in societies where religion and conservative ideals are so deeply entrenched, as in Malta – are brought into the picture, people react and spread information much faster. And when that information is in a visual form, even more so.

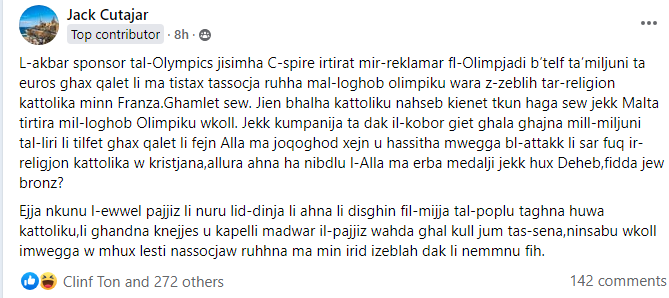

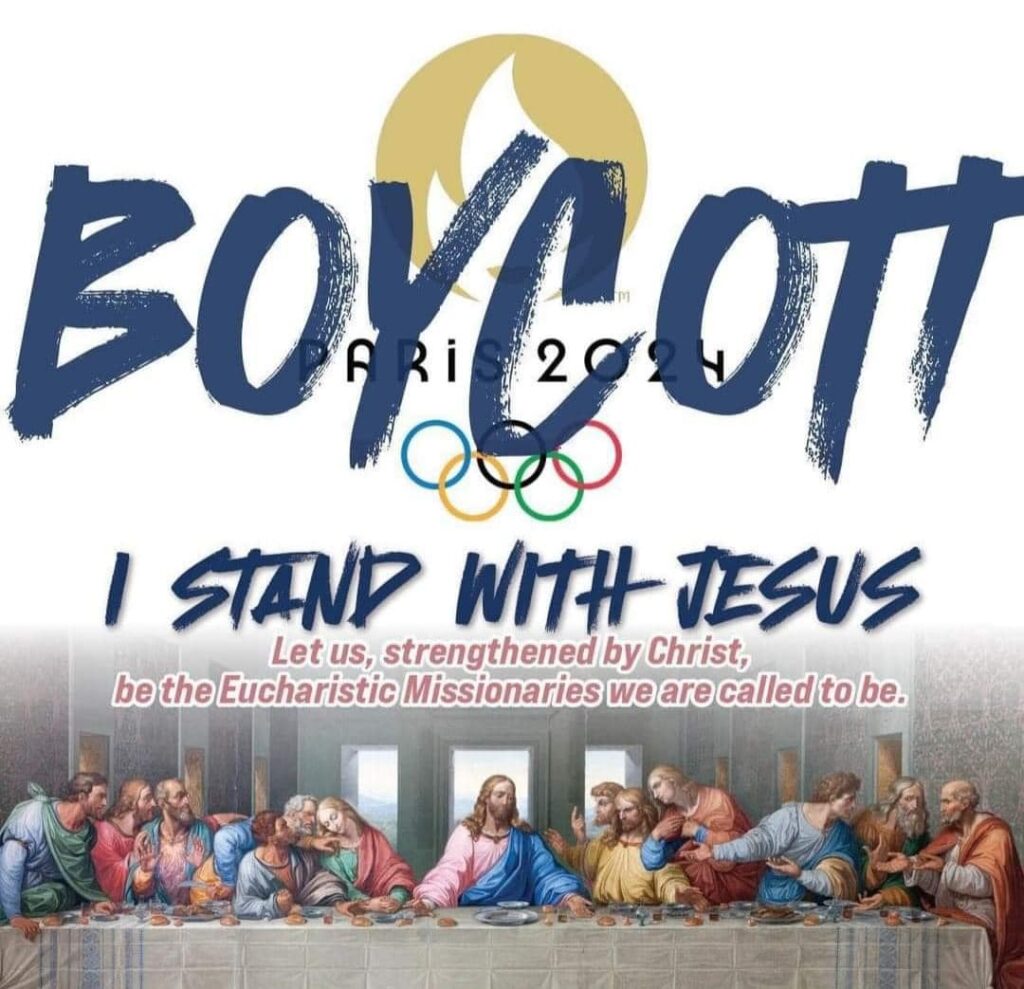

Posts condemning the segment as a ‘disgusting’ offence to Christianity have spread across Facebook in Malta. Some described the ceremony as ‘anti-Christian’, predictably blaming an unnamed ‘woke brigade’. Others called on Malta to withdraw from the games altogether. Similar comments have been posted under posts sharing news articles about the story.

Meanwhile, one particular local evangelical pastor is calling on people to boycott the Olympics.

Malta’s archbishop wrote to the French ambassador to Malta to express his ‘distress and great disappointment at the insult’. The French embassy responded by saying that it is ‘sorry that Christians felt offended’ and made reference to the explanation given by the opening ceremony’s artistic director, namely that the segment was in fact inspired by Greek mythology.

The Paris Olympics organisers have also issued an apology for unintentionally causing offence, and they too insist that the segment was not meant to parody Da Vinci’s painting and the biblical story said painting depicts.

It is interesting to understand why people are more ready to believe that the ‘Festivité’ segment was inspired by a biblical story and Da Vinci’s ‘Last Supper’ rather than by Greek mythology and paintings like Jan Harmensz van Bijlert’s ‘The Feast of the Gods’. After all, the Olympics originate from ancient Greece – and the singing man hidden beneath the giant cloche was a clear reference to Dionysus, god of festivities, who, as the opening ceremony’s artistic director explains, also happens to be the father of the goddess of the Seine, over which this performance took place.

Van Bijlert’s painting, which incidentally hangs in France, shows a hedonic scene of gods gathered around a table, dancing and gossiping as the sun god Apollo, aptly fitted with a halo of light, sits at the centre. If you were to read even more deeply into the image, you might even say that Apollo’s lyre finds its equivalent, in the Paris segment, as the central figure’s DJ equipment.

Following the controversy, Musée Magnin posted images of Van Bijlert’s work on X. ‘Does this painting remind you of something?’ the museum wrote, adding a wink.

A lot, perhaps even too much, has been said on the case of the Paris ceremony controversy already. Rather than proving or disproving the claim that it was meant as a parody of an important biblical moment – although, as explained, organisers deny it – we believe that there is more value in using this case to illustrate the potency of narratives repeated often enough, and the ways in which visual information can be reframed.

People generally see what they want to see and believe what they want to believe. It’s human nature. All we can do is pause before reacting.