Independent MP Rosianne Cutajar has taken to social media over the past few weeks to point fingers at opposition MPs who hold government jobs.

Cutajar was reacting to the publication of a report by the Auditor General that found her employment as consultant with the Institute of Tourism Studies to be “fraudulent” and “irregular”.

A one-time parliamentary secretary, Cutajar was a Labour Party backbencher until she stepped down from the party’s parliamentary group in April.

In her posts, Cutajar asked whether opposition MPs are reporting for work, pointing to several cases of MPs allegedly carrying out political activities during working hours.

Shortly after the publication of the Auditor’s report, the opposition gave notice of a parliamentary motion calling on Cutajar to return the money she was given for the consultancy. Labour whip Andy Ellul was quick to reply, quipping that the opposition should amend the motion to also include its own MPs who are on the state payroll.

The controversy has led to many wild and often conflicting claims about which MPs are currently employed by the government or hold roles with public bodies, as well as the nature of their alleged employment. As MPs on both sides bickered over the issue, misinformation about the issue has become widespread amongst the supporters of the two main political parties, with each pointing fingers at the other.

21 MPs employed or engaged by a public body

A series of parliamentary questions filed by Cutajar herself revealed that 13 opposition MPs are currently employed by the government in some role or other.

But that’s only half the story, since the parliamentary questions did not ask about government MPs.

In total, some eight government MPs are either employed by the government or appointed to chair a state entity.

This means that, excluding the 25 government MPs who are members of cabinet, eight out of the 18 government backbenchers hold a government role.

Click here to view a full list of MPs who hold a government role.

These include Omar Farrugia, who was controversially appointed chairperson of SportsMalta in recent weeks, and Chris Agius, who is the chairperson of Yachting Malta. Both of these are part-time roles for which they are paid honoraria. Meanwhile, opposition MP Toni Bezzina sits on the warranting board for architects.

Times of Malta is informed that no other MPs from either side of the House currently sit on government boards.

The exception to this are boards to which the government and opposition each nominate a representative, such as the Lands Authority board, to name one example.

The list also does not include MPs employed at the University of Malta which, although falling under the Education Ministry, has an autonomous governance structure.

PN MP Claudette Buttigieg, whose name has already been bandied around in the ongoing debate, is a senior executive at the university’s research trust, RIDT, while PL backbencher Katya De Giovanni is a senior lecturer in psychology. Meanwhile, PN MP Mario De Marco is listed as a visiting lecturer in law.

What about consultants?

The list also does not include consultancy roles, such as the one which was used to disguise Cutajar’s phantom job.

Research carried out by Times of Malta suggests that it is likely that no MPs from either side of the House are currently engaged as a consultant to a public entity or ministry, however this cannot be completely excluded.

For instance, it is unclear whether any MPs are providing a service to a government entity indirectly through their involvement with a firm or agency, rather than in their own name.

More broadly, the practice of engaging MPs as consultants is not new.

Current economy minister Silvio Schembri was controversially engaged as a consultant by his predecessor Chris Cardona when Schembri was first elected in 2013.

In 2019, Times of Malta reported that over two-thirds of parliament received some form of income from a government role, including several who were engaged as consultants or legal advisors to public entities.

Are these all phantom jobs?

No, it would be unfair to use Cutajar’s case to tar all MPs with the same brush.

Several of the MPs on both sides are believed to be experienced within their fields and many were already in their roles before they were ever elected to parliament.

But that’s also not to say that there aren’t any cases of abuse.

In 2020 Times of Malta reported that several opposition MPs seldom showed up for work, with then-PN MP Kristy Debono coming under the spotlight for rarely reporting to work.

This sparked an investigation by then-standards commissioner George Hyzler, which found that aside from Debono, David Agius and Ivan Bartolo also frequently did not show up for work. However, the report offered some mitigating circumstances in both cases.

Hyzler said that Agius’ role as party whip and, later, deputy party leader constitutes a “grey area” in terms of whether or not his frequent absences from work were justified.

Meanwhile, Bartolo’s absences were said to be a result of the “extraordinary amount of social work” that he carried out. While stopping short of justifying Bartolo’s behaviour, the report argued that “it would be unfair to typecast Mr Bartolo as a self-seeking individual who is abusing his position for his own benefit”.

An earlier report by the standards commissioner had looked more broadly into the widespread practice of backbench government MPs being given a public role of some sort, whether through regular employment or as a consultant, service provider or person of trust.

It found that two-thirds of backbench MPs were employed or engaged by the government at the time. This practice, the commissioner argued, was “fundamentally wrong”, runs counter to the Constitution’s underlying principles and erodes parliament’s ability to scrutinize the government’s work.

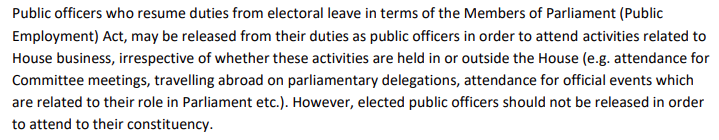

Are MPs allowed to skip work?

Only in specific cases.

The public sector rules say that MPs who are public employees can be given special leave to attend parliamentary sittings and official events related to their role as MP.

But the rules also clearly state that this doesn’t give them the right to skip work to attend constituency activities.

So, in practice, an MP can skip work to attend parliament, travel abroad as part of a parliamentary delegation or attend official events, but not to man their constituency office, attend local events or campaign.

Verdict

Of the 79 MPs sitting in parliament, 21 are currently employed or engaged by a public entity, or sit on a government board.

A handful of others work at the University of Malta which, although a public authority, has an entirely separate governance structure from the rest of the public sector.

Research suggests that no MP from either side of the House is currently engaged in a consultancy or advisory role with a public body.

Public sector rules say that MPs can skip work to carry out their parliamentary duties, but not for constituency work.

The Times of Malta fact-checking service forms part of the Mediterranean Digital Media Observatory (MedDMO) and the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), an independent observatory with hubs across all 27 EU member states that is funded by the EU’s Digital Europe programme. Fact-checks are based on our code of principles.

Let us know what you would like us to fact-check, understand our ratings system or see our answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the service.