False claims that a Roman chalice actually hails from ancient Greece and boasts mysterious colour-changing properties returned to social media in January 2023, following the latest talks over the British Museum’s possible return of the Parthenon sculptures to Athens. In reality, the ancient cup has been dated back to Roman times in the 4th century AD, is known as the “Lycurgus Cup” and has been proven by scientists to change colour in different lighting thanks to traces of silver-gold alloy in its glass front.

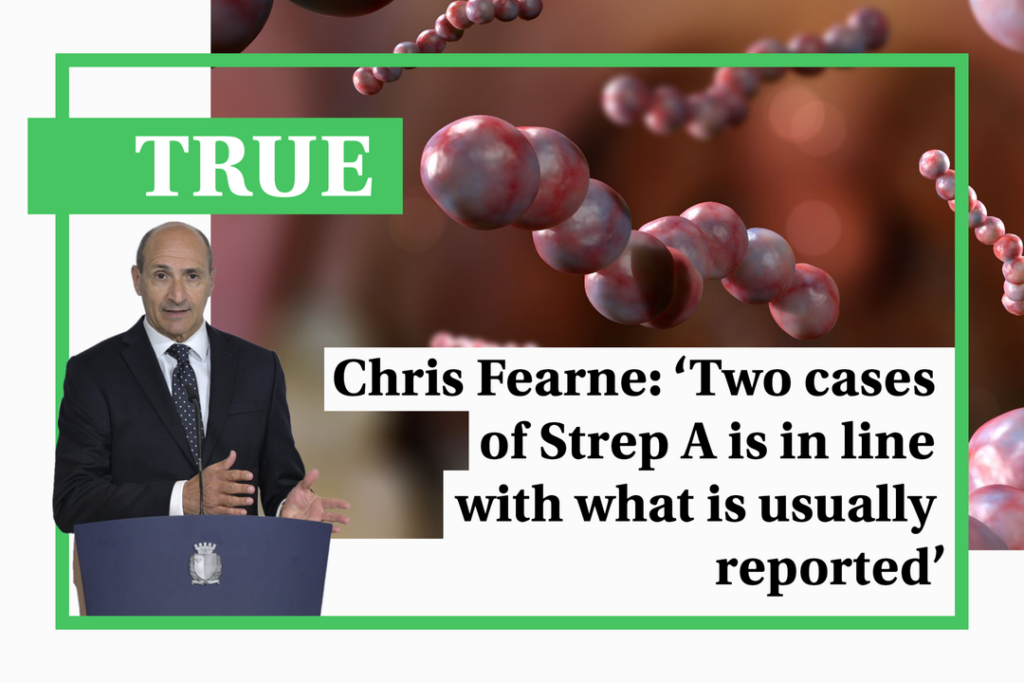

A Facebook post published on 15 January, 2023 shows a picture with two images of the ancient cup, one in which the cup is green and the other red. The following text in Greek accompanies the image: “IT IS EXHIBITED IN THE LOUVRE IT CHANGES COLOURS ALL DAY LONG IT IS THE GRAIL OF AGESILAUS OF SPARTA. THEY STILL DON’T KNOW WHAT MATERIAL IT IS MADE OF… KNOWLEDGE OF GREEKS”.

AFP found that the picture actually shows a screenshot of a 2020 Facebook post. The February 2020 post uses misspelled words and capital letters that match the screenshot shown in the recent posts, while on the upper part of the screenshot we can see the dateline of the post: “27 Feb 2020”.

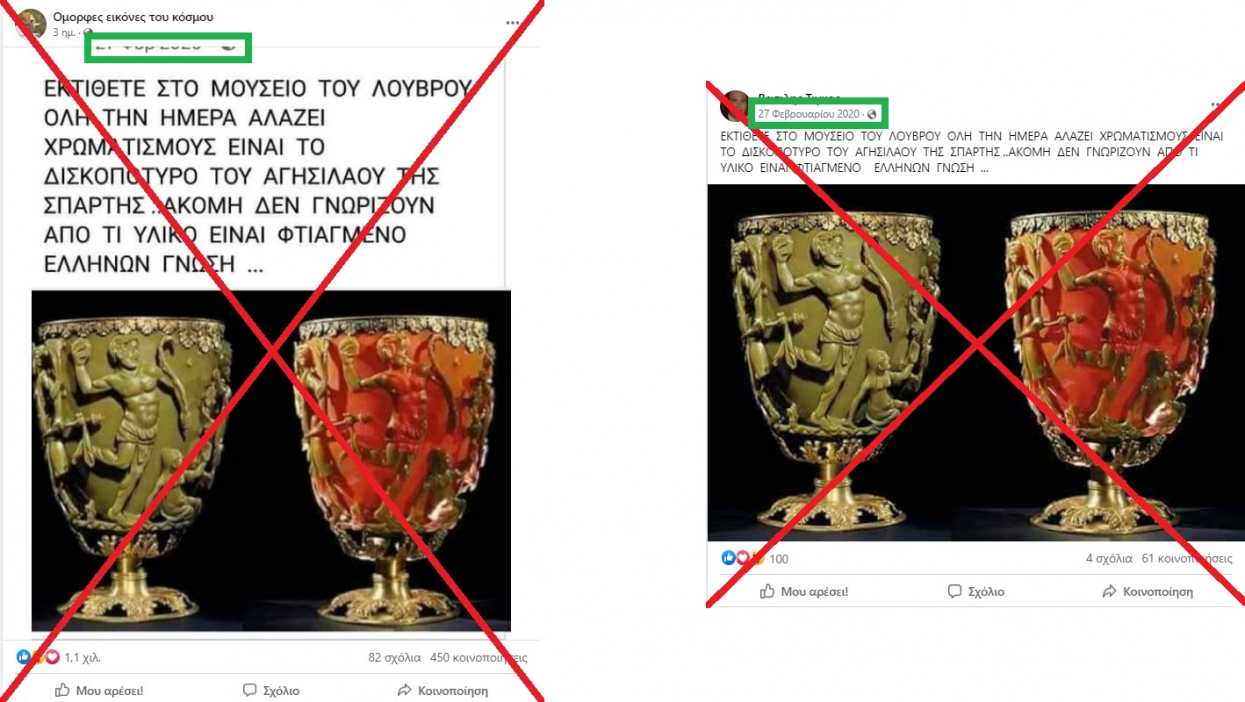

Several comments under the post mock the original post’s bad spelling, but others believe the claim to be true. “Grails in the Louvre, marbles in England and how many others in museums (because they stole them)” reads a comment, making reference to the Parthenon sculptures that are exhibited in the British Museum in London, an issue that Greek governments have historically tried to solve to no avail.

The post from January 2023, which has been shared more than 450 times, is only the most recent example of the same piece of misinformation. The same screenshot has previously been shared by many social media users, for example in January 2021 and in August 2022.

What does the picture actually show?

Reading through the comments under the posts with the false claim, AFP found this blog post, which suggests that the artefact shown in the picture is actually called “The Lycurgus Cup”. We then searched on Google for “Lycurgus Cup”, confirmed that it is indeed the same artefact and found more information about it.

The British Museum has a page dedicated to the cup on its website which states that it is currently on display in section G41/dc11 of the museum, in London.

“The Lycurgus Cup” takes its name from the mythical king of Thrace, Lycurgus, whose death is represented on the chalice. A book titled “New Light on Old Glass: Recent Research on Byzantine Mosaics and Glass”, which was published in 2013 by the British Museum, states: “The cup’s subject matter is the myth of Lycurgus, already recounted in Homer’s Iliad (6.130−40), but in a form that seems to follow closely the version known from Nonnos of Panopolis, who was writing roughly in the period when the cup was made at the end of the 4th or first half of the 5th century.”

According to the myth, Lycurgus had a feud with Dionysus, god of wine, theatre and sex. In Nonnos of Panopolis‘ version of the myth, Lycurgus died when, during a fight with the nymph Ambrosia, she turned into a vine and entangled him. “The cup shows Lycurgus entwined, with Ambrosia to his right on the ground beneath a satyr who attacks the king with a stone. To Lycurgus’ left is Pan with a panther and behind Pan, on the opposite side of the cup to Lycurgus, is Dionysios himself,” reads the British Museum’s publication.

Despite referring to a Greek myth, researchers have concluded that the cup is not actually from Greece. This study of the artefact, published in 2007 by Ian Freestone, Nigel Meeks, Margaret Sax and Catherine Higgitt, describes the cup as an example of late Roman cut glass. Even though its exact origin remains unclear, researchers D.B. Harden and J.M.C. Toynbee have suggested that the Lycurgus cup was manufactured in Italy, but they also considered the possibility of it coming from Alexandria.

The British Museum acquired the Lycurgus Cup from Victor, 3rd Lord Rothschild, in 1958. As the British Museum mentions in its website dedicated to the cup, the artefact “was originally acquired by Baron Lionel Nathan de Rothschild (1808-1879)”.

The Lycurgus Cup belongs to a class of Roman vessels known as cage cups or diatreta, explains the 2007 study. This classification is due to its decoration, which stands out of the vessel’s body. The Lycurgus Cup is considered the most elaborate and well-preserved cage cup of that era. “Cage cups are generally dated to the fourth century A.D. and have been found across the Roman Empire, but the number recovered is small, and probably only in the region of 50-100 examples are known,” notes the study.

“The only known glasses from the ancient world with parallel technologies and colour effects are Roman. In conclusion, the Lycurgus Cup is from the 4th century AD, most probably from Rome,” Ian Freestone, Professor of Archaeological Materials and Technology at University College London and one of the study’s authors, said in an email to AFP on 25 January, 2023.

The false social media posts incorrectly claim that the artefact is called “the grail of Agesilaus” and that it belonged to the Spartan king Agesilaus II, who reigned from 399 to 360 BC, several centuries before the creation of the Lycurgus cup. AFP looked online for archaeological artefacts related to Agesilaus II but did not find any relevant references.

Nanoparticles responsible for colour-changing properties

The Lycurgus Cup is known for its colour-changing properties, which have been studied by scientists. It appears jade green when lit from the front, but its colour changes to a ruby red when the light comes from behind, explains this article on the artefact published by the Smithsonian Magazine in 2013.

According to the 2007 study, “only a handful of other ancient glasses, all of them Roman, change colour this way”. The Lycurgus Cup is made from glass which contains nanoparticles of a silver-gold alloy, which gives it colour-changing properties, it notes. “X-ray analysis showed that these nanoparticles are silver-gold alloy, with a ratio of silver to gold of about 7:3, containing in addition about 10% copper,” the study reads.

“There is no doubt that the red colour is due to the presence of nanoparticles of a silver-gold alloy in the glass, these have been demonstrated by electron microscopy. The colour effects have been replicated in a number of laboratories by experiment,” Ian Freestone confirmed to AFP.

The same was confirmed by Jas Elsner, senior research fellow at Oxford University’s Corpus Christi College. “It has been proved by recent science that it is indeed glass with nanoparticles of gold, silver and manganese that make the effects,” he said in an email to AFP on 25 January, 2023.

The claim that the materials used for the manufacture of the Lycurgus Cup remain unknown, is therefore false. Scientists have proven that the Lycurgus Cup is made from glass and silver, and that its colour-changing property is derived from the nanoparticles in the glass.

Trend in false claims around ancient Greece

The recent posts with the false claim about the cup appeared at a time when the debate over the return of the Parthenon sculptures has been reignited, after reports claimed that Greece and the British Museum were close to striking a deal for their return to Greece under a loan agreement. Some comments under the posts specifically refer to the Parthenon sculptures, which Greece has long tried to reclaim since they were removed from the Parthenon by Lord Elgin in 1801 and offered to the British Museum.

Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis recently appeared optimistic regarding the return of the sculptures to Greece and said that “if the people trust us again, I believe that we will be able to achieve this goal [of the sculptures’ return]”, referring to the upcoming parliamentary elections set to be held in the spring of 2023.

The scientific and cultural sophistication of ancient Greece is often used as a basis for baseless claims that certain technological advances, even laptop computers, originated in ancient Greece. Claims that there was an “otherworldly” presence, also circulate, such as in this post which suggests that UFOs were present in ancient Greece.

Ancient Sparta, which is mentioned as the origin of the cup in the false claims, is often characterised as militaristic and warlike, and has become a subject of admiration particularly for the political far-right in Greece and abroad, as explained by Stephen Hodkinson, an expert in ancient Sparta and professor of history at the University of Nottingham, and Curtis Dozier, assistant professor of Greek and Roman Studies at Vassar College in New York, in an interview with Kathimerini. The ancient city-state has also been greatly popularised by the graphic novel “300” and the movie of the same name starring Gerard Butler as Leonidas, King of Sparta.

AFP has previously debunked false claims regarding archaeological artefacts from ancient Greece here.