The announcement on 6 May that Steward, the US health care conglomerate that was granted a concession to run three of Malta’s public hospitals, had filed for bankruptcy in the US led to fresh speculation over what would have happened to the hospitals if the deal were still in place.

The “fraudulent” deal was scrapped by courts in a landmark decision in early 2023, with the government immediately retaking control of the hospitals. The court’s initial decision was confirmed on appeal later in the same year, with courts finding “collusion” between government officials.

Things took a new turn in recent weeks, with a magisterial inquiry into the deal leading to criminal charges against dozens of individuals, including top government figures, linked to the deal.

Just days later, Steward announced that they had filed for bankruptcy in the US, having amassed some $9 billion in debt. The company later revealed that it had put all of its 31 hospitals in the US up for sale, in an attempt to cover some of their debts.

This news led many to speculate on a theoretical scenario where the three hospitals were still in Steward’s hands.

Some claimed that if the court case to scrap the deal, initiated by then-PN leader Adrian Delia, had not taken place, the three hospitals would currently be up for sale, together with Steward’s 31 other hospitals.

Others yet suggested that the hospitals would have been sequestered and handed to an administrator, and potentially used to pay off the company’s creditors.

What does the concession agreement say?

First of all, the agreement makes it clear that the deal was a time-bound concession, not a permanent transfer of property.

The contract says that once the 30-year concession period ended, the government “shall retain the option to request the reversion of the title” of the three hospitals.

In short, the government was transferring the three hospitals and their running to Vitals (and, later, Steward) for 30 years. But the hospitals would, ultimately be returned to the government after the concession elapsed.

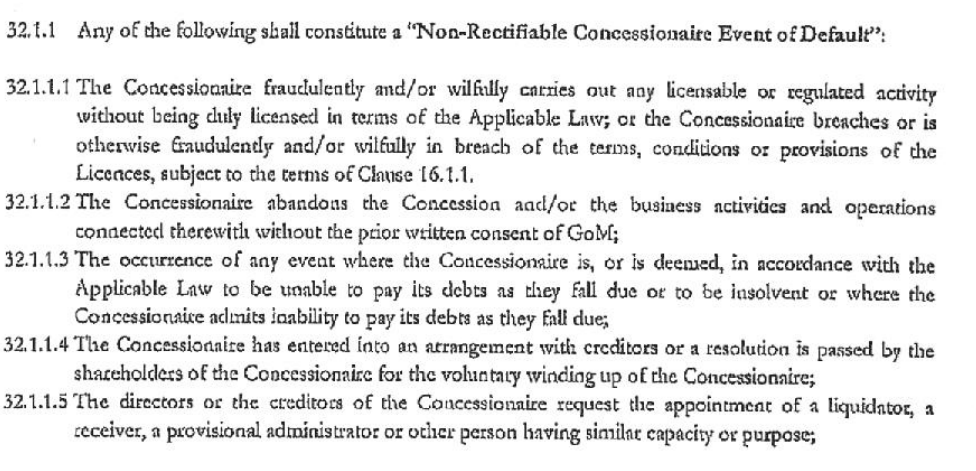

The concession agreement also talks about what should happen if Steward were to become insolvent, precisely the scenario that transpired last week. Insolvency is specifically listed in the agreement as one of several examples of a default.

Some defaults can be fixed, but insolvency isn’t one of them

The agreement distinguishes between a “rectifiable default” and a “non-rectifiable default” in this respect.

The former includes Steward’s well-documented failure to meet the milestones set in the agreement, including carrying out the investment it had promised. A rectifiable default meant that the government could intervene to find a suitable solution, but not to re-take control of the hospitals.

But insolvency is another matter altogether.

Insolvency is listed as one of the several instances defined in the agreement as a “non-rectifiable default”.

In these instances, the agreement says, the government “shall take control of the Sites and the Concession Services and Healthcare Services”.

When this happens, the agreement says, the government “shall be entitled to terminate the Transaction Agreements”, effectively bringing the entire deal to an end.

How would this happen in practice?

The contract, and a 2021 NAO report about the contract, lays out a blow-by-blow account of how this would play out.

The government would need to issue a termination notice setting out a date by which the agreement would be cancelled and then call on the performance guarantee “up to the Concessionaire’s financial indebtedness towards the Government”.

However, the government would essentially have to assume Steward’s debts on the project, meaning that it would need to pay off Steward’s €36m BOV loan – something that appears likely to happen in any case.

The auditor general described this drily as “onerous on the burden of risk to be assumed by the Government”, despite the government insisting that this is standard practice in this type of project.

What about the secret €100m exit clause?

But this is different to the infamous €100m clause engineered behind closed doors by then-Minister Konrad Mizzi.

That clause protected Steward and BOV in the case of a contractual default by the government, effectively meaning that the government would have to pay €100m if it wanted to scrap the deal for whatever reason, including because Steward was failing to meet its milestones.

This clause was to potentially also apply if the deal was struck down by courts, as would later transpire. Arbitration proceedings over the matter are ongoing at the International Chamber of Commerce.

But this €100m clause would likely not come into play when the default is triggered by Steward, rather than the government, as would happen in the case of Steward’s bankruptcy.

Verdict

The deal’s contract clearly describes Steward’s insolvency as a “non-rectifiable default”, meaning the government would be able to step-in and immediately scrap the deal by issuing a termination notice.

In that scenario, the government would have retaken control of the hospitals, effectively mirroring what happened when the deal was scrapped by Malta’s courts in early 2023.

However, the government would have had to assume Steward’s debts on the project, making it likely to have to fork out some €36m to cover a pending BOV loan, amongst other things.

But the €100m exit clause engineered by former Minister Konrad Mizzi would not apply in this case, since the default would be triggered by Steward, not the government.

The claim is therefore false, as the evidence clearly refutes the claim.

The Times of Malta fact-checking service forms part of the Mediterranean Digital Media Observatory (MedDMO) and the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), an independent observatory with hubs across all 27 EU member states that is funded by the EU’s Digital Europe programme. Fact-checks are based on our code of principles.

Let us know what you would like us to fact-check, understand our ratings system or see our answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the service.