Several social media and blog posts over the past weeks have been repeating false claims that a looming agreement will grant the World Health Organisation authority over Malta’s healthcare policy.

The claims say that the agreement will override Malta’s constitution and grant WHO unbridled decision-making powers to mandate vaccinations and take other healthcare-related decisions that would impact Maltese citizens. This, they say, includes mandating vaccine jabs for anyone over the age of six months.

Others say that countries such as Estonia and Slovakia have already rejected the treaty, citing a letter allegedly signed by several Estonian parliamentarians.

Meanwhile, in a recent post, blogger Simon Mercieca argued that “no one can deny that the amendments to the International Health Regulations (2005) and the introduction of the new Pandemic Agreement have the potential to hand nearly unlimited powers to the World Health Organisation”.

The claims refer to the so-called pandemic treaty, an international agreement aiming to make sure that countries will be adequately prepared for a potential outbreak of another pandemic in the future.

Misinformation about the treaty has been widespread ever since it was first announced. Earlier this year, Associated Press debunked a claim about the treaty signing away US national sovereignty, with Reuters also having found several similar claims to be false.

Times of Malta has previously fact-checked a similar claim made in an online petition that was circulated some months ago, finding that the proposed treaty cannot supersede Malta’s constitution. At the time, it was claimed that governments needed to respond to WHO’s request by 31st October to maintain sovereignty over their healthcare policy.

With that deadline having come and gone, several posts now say that the government has until 1st December to file its objections or opt out of the agreement, before it comes into force.

What is the pandemic treaty?

The idea of an international treaty arose in May 2021, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the time, the international community was caught unprepared by the scale of the pandemic and, as a result, many countries were slow to react to the spread of the virus.

Following this wakeup call, international health authorities, including WHO, launched initial discussions over the treaty, hoping that it would increase early detection and provide equitable access to medicines across the globe, if a similar pandemic were to occur again.

A first draft of the treaty, known as the zero draft, was published earlier this year, outlining the key concepts of the treaty. The final text of the treaty is still being negotiated but is expected to be signed at the May 2024 World Health Assembly.

What is WHO’s role in the treaty?

While WHO is leading the negotiation process, it is not actually a party to the treaty, contrary to popular belief.

In reality, the treaty is an agreement between different countries that are members of WHO, rather than an agreement with WHO itself.

This means that the terms of the deal will be determined by the individual countries currently negotiating the deal, not by WHO.

Likewise, negotiations are not carried out behind closed doors, as some suspect, but are painstakingly documented on the website of the dedicated Intergovernmental Negotiating Body that was set up to lead discussions.

Meetings are recorded and streamed on the website and notes from the meetings are published regularly.

What does the treaty talk about?

In practice, the treaty deals with how countries can better coordinate and fund their response to a pandemic.

This includes establishing clearer guidelines on how a pandemic is defined, the procedures to be followed when declaring a pandemic, and how to ensure fairer access to technology and medication.

The draft treaty proposes several ways to do this. Proposals include financing more research into pandemic-related issues, communicating information about potential pandemics through clearer communication channels and dashboards, and smoothing out supply chain and logistical issues that could hamper the delivery of medication.

The draft treaty does not talk about lockdowns, vaccine mandates, or the surveillance of citizens, nor does it mention specific measures like contact tracing and face masks in its recommendations.

It also does not include or propose any mechanisms that would force countries to follow the treaty’s recommendations or punish them if they stray from the recommendations. This has led some critics of the treaty to accuse it of being toothless and unlikely to be effective.

Ultimately, the treaty wants to make sure that countries around the world will be better placed to deal with an outbreak similar to that of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What does the treaty say about countries’ sovereignty?

Quite a lot, in reality.

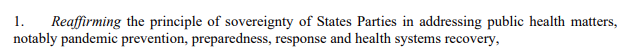

The draft text doesn’t shy away from the issue, with the very first point in its opening chapter at pains to highlight the sovereignty of countries to establish their own healthcare policies and decide on “public health matters, notably pandemic prevention, preparedness, response and health systems recovery”.

The text later lists sovereignty as one of its guiding principles, saying that countries have “the sovereign right to determine and manage their approach to public health” as well as over “their biological resources”.

A correspondence note published in September by The Lancet, a world-leading medical journal, elaborates on this, saying that the “bureau text includes provisions safeguarding national sovereignty, which has been consistently emphasised by the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body (INB) during negotiations”.

What about amendments to the International Health Regulations?

A separate working group is also working on amendments to the International Health Regulations, a set of rules placing certain obligations on member states in the face of public health events.

These amendments have also been the subject of misinformation, with some arguing that they are being used to introduce restrictive measures that would grant WHO power over its members.

A review of the proposed amendments shows that the opposite is actually true. The amendments include adding several clauses specifically outlining that any recommendations must respect the sovereignty of individual countries.

Verdict

The draft pandemic treaty repeatedly outlines the sovereignty of individual countries and lists national sovereignty as one of its guiding principles.

Likewise, parallel amendments to the International Health Regulations are proposing additions that include clauses highlighting the need to respect national sovereignty.

The treaty does not impose any measures such as lockdowns, vaccine mandates or other restrictive measures. It also does not propose any punitive measures for countries not following its recommendations.

This claim is therefore false, as the evidence clearly refutes the claim.

The Times of Malta fact-checking service forms part of the Mediterranean Digital Media Observatory (MedDMO) and the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), an independent observatory with hubs across all 27 EU member states that is funded by the EU’s Digital Europe programme. Fact-checks are based on our code of principles.

Let us know what you would like us to fact-check, understand our ratings system or see our answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the service.