Reacting to the driving test racket revealed by Times of Malta on October 1, Prime Minister Robert Abela defended ministers and public officials who helped people get fast-tracked for their driving tests, saying that customer care officials were simply doing their job.

This claim was repeated by several other Labour Party MPs over the following days.

The racket was revealed after leaked WhatsApp chats showed then-transport minister Ian Borg and several members of his secretariat feeding names to Malta’s transport authority seemingly in an attempt to help candidates obtain a driving licence.

Several people implicated in the scandal were engaged as officials within minister’s secretariats and customer care units, including Ray Zammit, a former customer care official at the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), Glorianne Micallef Portelli, the head of customer care within Ian Borg’s ministry, and Joseph Mangion, who worked within Borg’s secretariat.

The scandal raises further questions about the role of customer care departments embedded within ministries and other public organisations.

Departments mired in controversy

While critics have long accused customer care departments of nurturing clientelism and encouraging political patronage, government officials say that they play a crucial role in ensuring that government organisations are sensitive to the public’s needs.

These seemingly mysterious entities have been linked to several controversies over the years, from then-Gozo Minister Anton Refalo employing his wife as a customer care officer in his own ministry, to former Health Ministry official Neville Gafà being transferred to OPM’s customer care unit following police investigations over alleged bribery.

They have also been suspected of funnelling voter data from government to political parties over the years. Testimony at a 2018 Public Accounts Committee hearing implied that the Environment Ministry’s customer care unit is occasionally in contact with that at the Labour Party headquarters.

More notoriously, a 2008 email from then Nationalist Party general secretary Paul Borg Olivier asked Cabinet members to forward the personal data of people who submitted complaints to ministries’ customer care units.

These controversies have led many to view ministerial customer care departments as a manifestation of clientelism in Maltese politics. As one Dutch academic argued, “a victory of a favored politician or party can entail several years of (privileged) access to state services, while a defeat can translate into years of exclusion”.

Why do customer care departments exist?

Long-serving public officials who spoke to Times of Malta say that customer care departments have been embedded within government ministries for decades, although their existence has only been formally documented in recent years.

These departments, sources say, serve multiple functions.

For one thing, they are intended to help ministers keep tabs on how their ministry is functioning and the bureaucratic or administrative hurdles preventing citizens from accessing government services. Secondly, they help ministers keep their finger on the pulse of their constituents, identifying pressing issues of concern within the community.

Officially, however, their purpose is quite opaque. Official documents fail to clearly outline the tasks that customer care departments are expected to carry out, nor do they provide any clear guidance on what sort of practices are forbidden.

Does each ministry have a customer care department?

Yes, every ministry engages a customer care official, although calling it a department might be a stretch.

Sources told Times of Malta that, unlike previous practice, the current administration has opted to also create a centralised government customer care unit based at the Office of the Prime Minister, ostensibly to streamline citizens’ concerns and better coordinate responses across different ministries and public bodies.

This is in addition to the government’s official customer care entity, today known as servizz.gov, which serves as a one-stop-shop where citizens can lodge complaints, seek help when dealing with public services and make suggestions about government services.

This service was initially launched in 2002 and refined throughout the years, with authorities at the time saying that they received over 100 requests each day.

The service remains staggeringly popular. Its latest annual report says that over 2,000 calls a day were received on its freephone number in 2022, along with hundreds of other requests through the service’s chatbot, email and other communication channels.

Who works in customer care departments?

Customer care units form part of a minister’s secretariat, meaning that customer care officials are handpicked by the minister and employed as persons of trust (if they are picked from outside the public service), or in a position of trust (if they are already public officials).

These officials are intrinsically tied to the minister’s fate, so once the minister changes, they automatically find themselves out of a job or – for those who already were government workers – returned to their previous role.

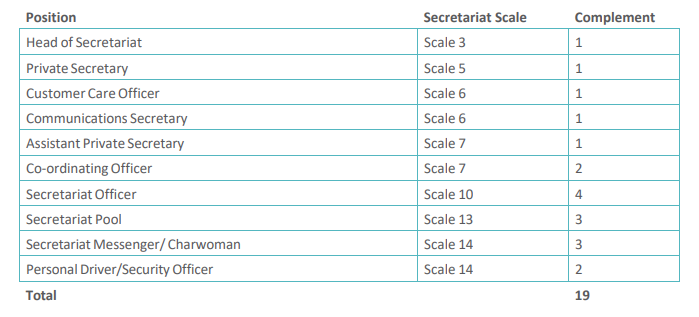

The Manual on Resourcing Policies and Procedures, published by OPM, says that each minister can employ one person in their secretariat to serve as a customer care officer, paid at a salary scale six (a maximum of some €32,500 before tax per year), together with just over €4,600 in allowances.

In total, a minister’s secretariat can consist of as many as 19 people, with other roles including communications staff, private secretaries and drivers or messengers.

Things are a little different when it comes to the OPM’s centralised government customer care unit, in which up to 18 customer care assistants can be employed at pay scale 11 (up to roughly €23,500 per year) to form the central government’s customer care unit.

In addition, the unit employs a head of customer care on a scale four pay packet (€38,400 per year, before tax), together with up to €6,300 in allowances.

Who or what rules regulate their conduct?

There are no specific guidelines for customer care officers and the parameters within which they operate remain a little hazy.

A 2021 guidance note by the Standards Commissioner says that while persons of trust fall within the office’s jurisdiction, people in a position of trust (people handpicked from within the public sector) do not.

This leads to an anomalous situation where different customer care officials are subject to different oversight, depending on whether they were previously public officials or not.

In any case, sources told Times of Malta that all officials paid by the government, including those employed on a basis of trust, are expected to abide by the code of ethics outlined in the Public Administration Act.

What does the code of ethics say?

This code declares that citizens “expect the departments and agencies of the Government of Malta to comply with the letter and the spirit of the law”, arguing that a public administration “rests on the extent to which it earns the respect of its citizens”.

It outlines several values that public officials are expected to demonstrate, including integrity, loyalty, trustworthiness and impartiality. Notably, it says that public officials are expected to ensure that the decisions they take are “not tarnished by personal bias” and not designed to “give any manner of unjustified preferential treatment to one person over another”.

Likewise, a 1994 code of ethics for cabinet members says that a minister “should never ask or expect members of the public service to do things […] which run counter to the objectivity and impartiality that are required of them”. Furthermore, the code says, the work of members of their secretariat “should never be that of promoting party politics” and its resources “should never be that of promoting party politics”.

This was expanded upon in a revised code of ethics published in 2019, which insists that ministers should not “make improper use of information they receive in their role to grant someone an undue advantage and disadvantage others”.

Different guidelines for public employees

The conduct of public employees is governed by the Quality Service Charter and several directives issued by the head of civil service from time to time.

These directives contain everything from seemingly pedantic instructions on how long it should take to answer a phone call (“within a maximum of three rings”) and what colloquial terms should be avoided (“dear” and “lovely” are out, but there’s no mention of “king”, a term frequently used in the leaked WhatsApp chats) to relatively clear guidelines on how public officials should communicate with members of the public, seemingly in an attempt to discourage informal unauthorised communication outside official channels.

These directives are aimed at government employees, not people who are employed on a basis of trust, suggesting that they do not necessarily apply to the members of ministers’ secretariats.

Verdict

Customer care units exist across the government, with each minister allowed to engage a person of trust to serve as a customer care officer within their secretariat. These units are intended to support the public in accessing public services, several codes of ethics and guidelines outline how this should not be done at the expense of placing other members of the public at a disadvantage.

In practice, their functions appear to be quite poorly defined. Nonetheless, ethical guidelines demand that government representatives avoid granting preferential treatment or tarnishing the integrity of their office in any way.

The Times of Malta fact-checking service forms part of the Mediterranean Digital Media Observatory (MedDMO) and the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), an independent observatory with hubs across all 27 EU member states that is funded by the EU’s Digital Europe programme. Fact-checks are based on our code of principles.

Let us know what you would like us to fact-check, understand our ratings system or see our answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the service.