Recent news about the development slated for Manoel Island, a small island in the north of the country, reignited debate over the project, with many claiming that the government can soon reclaim ownership of the land from MIDI, the private company that was granted a concession for the development.

On 14 March, a decision on a permit application for the building of new residential blocks on the island was deferred by the Planning Authority over concerns over whether or not the island falls within a proposed UNESCO buffer zone for the capital city of Valletta.

This is only the latest twist in the controversial development, with environmental NGOs Moviment Graffitti and Flimkien Għal Ambjent Aħjar saying that the development could endanger Valletta’s heritage status, in a debate reminiscent of the later-revoked permit for an apartment block metres away from the Ġgantija temples in Gozo.

This has spurred several online discussions over the future of Manoel Island, with some suggesting that the government could buy the land back and others saying that the government can scrap the deal entirely because of the project’s delays.

Speaking to Times of Malta on Wednesday, Prime Minister Robert Abela brushed off questions over the project’s deadlines, saying that contractual obligations need to be respected, despite his reservations over the “obscene” concession.

Questions sent to the Prime Minister’s office about the matter, including whether the government would be inclined to extend or rescind the concession, were redirected to the Lands Ministry for technical information on the concession, with a spokesperson pointing to Abela’s comments on Wednesday.

What does this all refer to?

The whole affair dates back almost a quarter of a century, when the government of the day granted developers MIDI a concession to develop the land on Manoel Island and at Tigne Point, an area in the seaside town of Sliema, back in June 2000.

Both sites were given to MIDI on a 99-year lease, a quarter of which has already elapsed.

The development at Tigne Point was eventually completed a little over a decade after the concession was signed, despite widespread criticism of the project’s visual impact (including by then MIDI chair Albert Mizzi, who euphemistically confessed to having “second thoughts about how it looks from Valletta”).

But the Manoel Island project has been stuck in limbo ever since the concession was signed, with the project never truly getting off the ground.

This isn’t to say that no work at all was carried out at the site over the past two decades. In early 2020, MIDI announced the completion of restoration works on Fort Manoel, an 18th century fort located on the island, together with that of several other historic structures.

But the site remains largely abandoned, with work on the project’s 323 residential units, restaurants, sports facilities, open spaces and marina all at a standstill and awaiting a development permit.

Permits for the works have been a long time coming.

The very first permit for the site was issued back in late 1999, before the concession was even formally signed off. That permit expired with little work having been carried out.

A staggering 17 passed before MIDI submitted a new masterplan for the site in 2017, with the permit being issued two years later, in 2019.

Things took an unexpected turn in 2020, when the permit was revoked after the Environment and Planning Review Tribunal annulled an environmental impact assessment carried out for the project, finding that it had been drawn up by the son of one of MIDI’s directors, raising concerns over a conflict of interest.

A new, revised masterplan was eventually submitted and finally approved in September 2021.

Last week’s deferral is the latest twist to the long-standing saga.

Throughout the years, several eNGOs and residents have objected to the project, with thousands signing a petition calling on the government to revoke the concession and turn the island into a park.

What does the concession agreement say?

The concession agreement lays out the project’s planned timeframes in meticulous detail, outlining the works to be carried out each step of the way and how long works in each of the island’s areas would take.

While the island’s northern marina and marina mall would be completed in a relatively speedy three years, those on the Lazzaretto and southern marina last for six years, according to the contract.

The contract says that MIDI was to apply for a development permit within a year of signing the concession agreement, with works to begin in the year after the permit was granted.

In the next four years, MIDI was to “substantially complete” works on Manoel Island’s southern marina, “which includes the new Manoel Island bridge, the dredging works between Manoel Island and Gzira and the Manoel Island breakwater”.

Are fines or deadlines mentioned?

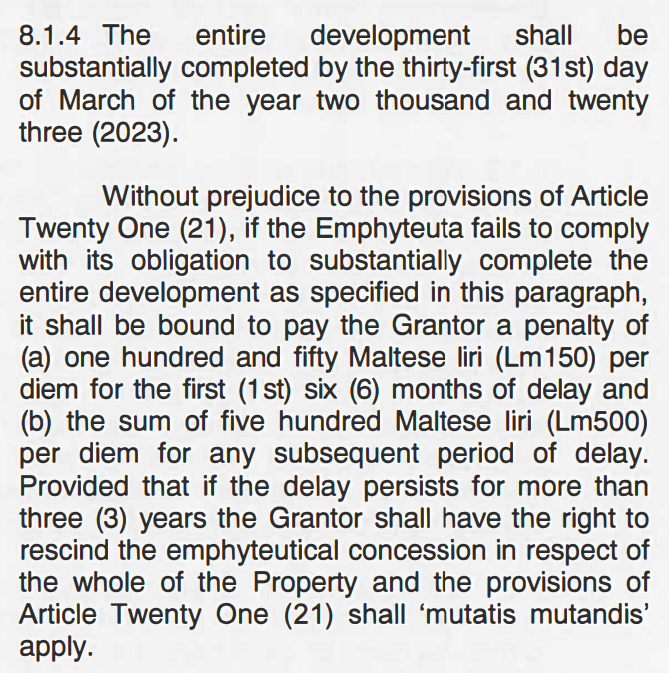

Ultimately, the contract says, the entire project was to be “substantially completed” by 31st March 2023, almost a year ago to the day.

If this isn’t the case, the contract says, the government would impose a daily fine of Lm150 (almost €350) for the first six months and Lm500 (just under €1,165) for every day after that.

To put things into perspective, this would have worked out to some €277,000 in fines over the past year.

Times of Malta asked both the government and MIDI if such fines have been imposed. An OPM spokesperson did not reply to that question while MIDI said the deed provided for an extension of time limits if permitting processes were delayed.

Significantly, the contract also says that MIDI have a further three years beyond the March 2023 deadline to carry out their work, bringing the ultimate deadline up to 31st March 2026.

If works still aren’t “substantially completed” by then, the concession says, the government can scrap the concession entirely at virtually no cost.

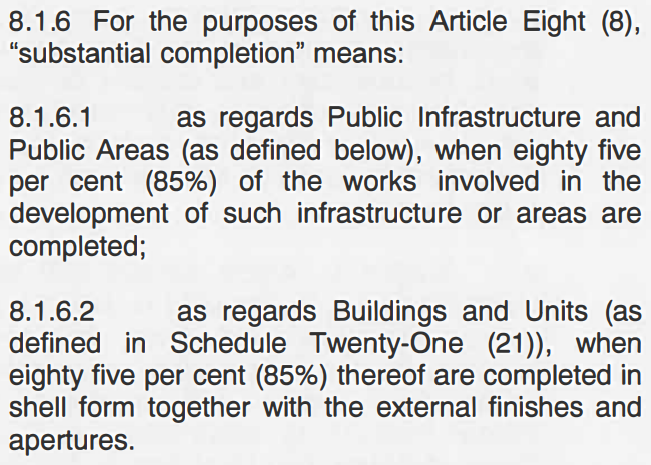

What does ‘substantially completed’ even mean?

This somewhat vague description has been the subject of some confusion in the online discussions that have taken place.

But the concession agreement dedicates several paragraphs to explain what it means by “substantially completed”.

In practice, the contract says, substantial completion means that 85% of public spaces are completed, as well as 85% of buildings being built in shell form with external finishes and apertures in place.

So, the concession says, MIDI have to complete 85% of the project over the next two years. Given that the development is yet to be granted a permit, it appears increasingly unlikely that the project will be anywhere near completion by the looming deadline of early 2026.

Are things that clear-cut?

MIDI certainly don’t think so.

In a statement posted last year MIDI acknowledged the March 2026 deadline set by the concession, arguing however that the timeframes are “directly linked” to each phase being granted a development permit.

In the same statement, posted after winning an appeal over the validity of an environmental impact assessment, MIDI accused environmental NGO Flimkien Għal Ambjent Aħjar of causing “vexatious and abusive” delays in the process by objecting to planning decisions “in the hope that the delays will negatively impact the time frames associated with MIDI’s development obligations”.

In written comments sent to Times of Malta, a MIDI spokesperson said that the concession states that “in the event of any delay associated with the issue of building and development permits required in connection with the development, the time limits for the performance of the relative obligations by MIDI shall be extended automatically to compensate for such delays”.

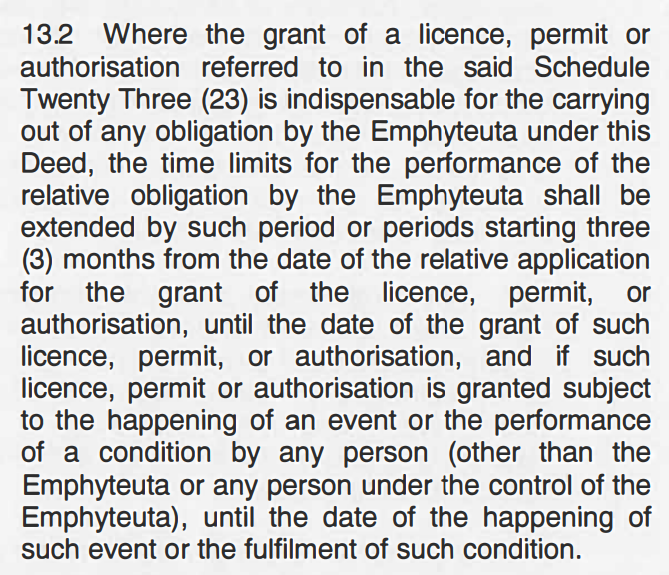

MIDI are referring to a clause in the agreement which says that where a permit is “indispensable” to carry out works, the project’s time limits “shall be extended by such period or periods starting three months from the date of the relative application […] until the date of the grant of such licence”.

The clause goes on to say that the extensions granted to MIDI are subject to them “having made and duly filed all applications for the aforesaid permits, licences or authorisations”.

In essence, MIDI argue, the March 2026 deadline doesn’t apply because the development permit for the project hasn’t yet been granted.

MIDI also told Times of Malta that the agreement “provides for an extension of time within which MIDI is bound to perform its obligations in the event of delays pursuant to discoveries of archaeological importance”.

“A number of archaeological finds were discovered during site investigations under the supervision of the SCH, which necessitated the complete redesign of the Masterplan,” the spokesperson said.

Verdict

The concession, signed in 2000, says that the project should have been mostly completed by 31st March 2023. If this was not done, MIDI would have to pay a daily fine and be granted a three-year extension until March 2026 to complete 85% of the works.

If the works are still lagging behind by March 2026, the agreement says that the government would have the right to scrap the deal and reclaim the land at virtually no cost.

However, MIDI says that these timeframes are tied to the project being granted a development permit. MIDI argues that a clause in the concession allows for these deadlines to be extended while permits are pending.

The project’s first development permit was issued in 1999, with a second masterplan drawn up almost two decades later, in 2017. Several delays have meant that the project is still waiting for a development permit to be issued.

The latest twist in the tale took place last week, when the permit application was deferred over concerns about whether the site is within a UNESCO buffer zone.

The Times of Malta fact-checking service forms part of the Mediterranean Digital Media Observatory (MedDMO) and the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), an independent observatory with hubs across all 27 EU member states that is funded by the EU’s Digital Europe programme. Fact-checks are based on our code of principles.

Let us know what you would like us to fact-check, understand our ratings system or see our answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the service.