The latest act in the long-standing dispute over the future of Ħondoq ir-Rummien, a picturesque bay on the island of Gozo, took place late January, with the Planning Authority shooting down the landowners’ claim that changing the area’s local plans infringes upon their property rights.

After almost two decades under the threat of development, a planning tribunal shot down development plans in 2022, with an appeals court confirming that decision a year later.

In January, the Planning Authority (PA) published a consultation document which would change the area’s local plans to forbid development in the bay or surrounding area and designate it as a site for afforestation, much to the dismay of aggrieved landowners.

A MaltaToday report into the dispute reported Gozo Prestige Holidays, who owned a tract of land in the bay which they once hoped to develop into a tourist village and marina, arguing that the PA’s move will deny them “property rights” to which they are entitled.

The PA rebutted by saying that since no development permits had been issued on the land, there are no automatic development rights.

The dispute strikes at the heart of the broader debate over whether local plans can be changed and what the implications of re-zoning would be.

Local plans ‘create rights for property owners’…or do they?

Local plans fundamentally set out which areas are open to development and which are to remain outside the development zone.

Malta’s local plans were drawn up in 2006, in a controversial move that saw large tracts of untouched land being included in zones earmarked for development.

While there have been adjustments to the local plans since, most notably a series of revisions published in 2015, authorities have ruled out carrying a drastic review any time soon. Prime Minister Robert Abela last year argued that doing so would cause “great injustice”, saying that the government “cannot revoke people’s property rights”.

Abela was even more unequivocal back in 2021, telling The Malta Independent that the 2006 local plans “created rights for property owners”, tying the government’s hands and making it difficult for local plans to be changed.

This is a rare case of an issue finding consensus across parliament’s benches. In 2021, Opposition leader Bernard Grech made the identical point, telling Times of Malta that “we cannot touch the rights that already exist”.

What do Malta’s laws say about property rights?

The highest law of the land, Malta’s Constitution, speaks of the rights of people not to be deprived of property without being compensated, saying that no property “shall be compulsorily taken possession of, and no interest in or right over property of any description shall be compulsorily acquired”.

In practice, this protects people from having their land expropriated or forcibly removed although, even in this case, the Constitution allows for some exceptions (for example, if taking over land would be in the “national interest” and the landowner receives “adequate compensation”).

The EU Charter of Fundamental Rights has a similar provision, saying that nobody can be deprived of their property, except in specific circumstances. It adds that the “use of property may be regulated by law in so far as is necessary for the general interest”

Neither document, however, specifically discusses the rights of landowners to develop their land.

So where does the ‘right to develop’ enter the picture?

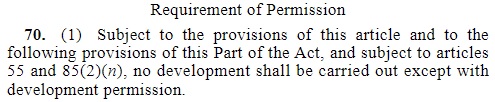

The right to develop in Malta is, in effect, held by the State, not the individual landowner.

Put simply, this means that individual landowners can’t decide themselves what to do with their land, but it is up to the State to set the parameters of what is and isn’t allowed on a tract of land.

This is where things like local plans and zoning enter the equation.

The State decides which zones in the country are open to development (and what particular types of development) and individual landowners within those areas then have the legal right to apply for a permit to build on their land and have their application evaluated by authorities.

All this emerges from Malta’s Planning Act, which clearly outlines how “no development shall be carried out except with development permission”, going on to say that the planning board has the right to grant or refuse a development application after consulting the country’s planning laws, policies and regulations.

In this respect, Malta’s planning system owes a debt to Great Britain, where legislation set up in 1947 effectively nationalised the right to develop land, placing the onus on local authorities to allow or refuse development. This is unsurprising, given that the first version of Malta’s Planning Act, which came into effect in 1992, was “based on the British system”.

Kamra tal-Periti (Chamber of Architects) president Andre Pizzuto made a similar point on several occasions, saying that “the basis of planning systems across the world is that development rights are de facto nationalised. While ownership of land and property is recognised as a fundamental human right, development is not a right vested in any individual”.

In practice, Pizzuto says, this right is held by the State and individuals “must request permission from the State before carrying out development”.

Are things really that simple?

They are at face value, though the lack of existing case law on the matter, coupled with the myriad complexities in land deals, means it is impossible to exclude that there could be particular circumstances in which a landowner can prove a vested right to develop, and successfully sue.

More generally, however, it is the political and economic considerations of any rezoning moves that are likely to prove the messiest to resolve.

This is where the “injustices” that both Abela and Grech refer to lie.

A person who owns land within a development zone does not have an automatic right to develop it, but they nonetheless own a piece of land that has the potential to be granted a development permit at some point in the future.

A change to local plans removing that potential is likely to strike a blow to the land’s financial value and could potentially prove unpopular amongst impacted landowners.

Verdict

The right to develop is not enshrined in any law, unlike other property-related rights, such as the right not to be forcibly deprived of property.

Malta’s planning laws say that a right to develop only exists after a development permit has been issued.

Malta’s planning laws, like those of many other countries around the world, do not provide an automatic right to develop. Development is only allowed once a development permit is issued, regardless of whether or not the area’s local plans say that development is allowed in that zone.

Changing an area’s local plans to prohibit development does not violate a landowner’s right to develop, but other factors, such as economic or political considerations, could mean that policy-makers are reluctant to do so.

The Times of Malta fact-checking service forms part of the Mediterranean Digital Media Observatory (MedDMO) and the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), an independent observatory with hubs across all 27 EU member states that is funded by the EU’s Digital Europe programme. Fact-checks are based on our code of principles.

Let us know what you would like us to fact-check, understand our ratings system or see our answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the service.