Following weeks of intense public pressure, Prime Minister Robert Abela announced on Monday that a public inquiry into the death of Jean Paul Sofia, a 20 year-old construction worker killed under the rubble of a building collapse in December, will take place.

The announcement came shortly before a vigil to mark Sofia’s death attended by thousands of people in the capital city of Valletta. The government had initially resisted calls for a public inquiry, but caved in following pressure from civil society, the opposition and Sofia’s family.

In a press conference held on Monday evening to announce the launch of the inquiry, Abela explained that the inquiry will be carried out under the Inquiries Act, the legal instrument that governs independent inquiries, and will be led by a three-person board.

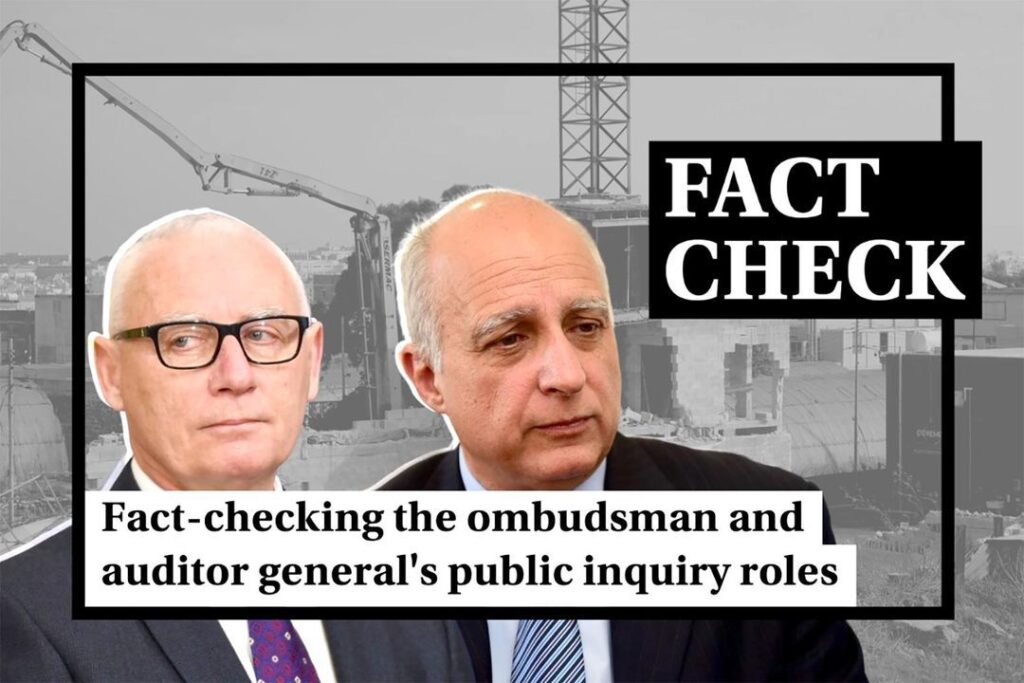

The profile of the board members raised eyebrows amongst some critics, who said that the law does not allow them to take on other roles or sit on the public inquiry’s board.

Who is on the board?

The board will be led by Ombudsman Joseph Zammit McKeon. He was previously a judge, having been appointed to the bar in 2009 and serving for 12 years until his retirement in 2021.

The second person on the board will be Auditor General Charles Deguara. He was appointed to this role in 2016, after having served as deputy auditor general for several years.

The third member of the board will be architect and court expert Mario Cassar. Cassar has served as a court expert in several high-profile cases, including the 2015 Paqpaqli għall-Istrina crash which injured 23 onlookers. Cassar was a member of the four-person board tasked with drawing up recommendations for excavation and construction practices following the building collapse which killed Miriam Pace when her home collapsed in 2020 under the strain of excavation works taking place next door.

Lawyer and former opposition MP Therese Comodini Cachia expressed her concern in a tweet, saying that while she doesn’t doubt the integrity of the individuals, their appointment to the inquiry is “constitutionally weird and dangerously touching on the stability of the constitutional institutions they run”.

What does the law say?

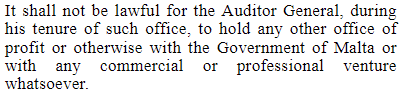

The role of the auditor general is a constitutional post, with Article 108 of the constitution outlining the duties of the post, as well as whether or not the post-holder can take on other roles.

The constitution prohibits the auditor general from holding “any other office of profit or otherwise with the Government of Malta or with any commercial or professional venture whatsoever”.

The ombudsman, on the other hand, is regulated by the Ombudsman Act, which describes the role of ombudsman as “incompatible with the exercise of any professional, banking, commercial or trade union activity, or other activity for profit or reward”.

It goes on to prohibit the ombudsman from holding any positions that may impact their “impartiality and independence or (with) public confidence”. However, it allows the ombudsman to take on any other “positions, trusts or memberships” that do not impact their impartiality, provided that they first seek approval from the Speaker of the House.

What do the office holders say?

Speaking to Times of Malta, Auditor General Charles Deguara brushed off concerns, arguing that this role is an assignment with a fixed term, not an office.

Meanwhile, a spokesperson for the ombudsman told Times of Malta that “the ombudsman finds no conflict of any nature in his position as ombudsman and in leading the Public Inquiry”.

Legal experts have mixed views

Several constitutional experts who spoke to Times of Malta had mixed opinions over the issue.

Joseph Said Pullicino, Malta’s Chief Justice until 2002 and a former ombudsman himself, believes that it is “difficult to reconcile the appointment of the ombudsman on the public inquiry with the Ombudsman Act”, arguing that there have been several cases in the past where people in similar roles were prevented from taking up additional roles because of the legal provisions precluding them.

Said Pullicino pointed to the fact that while the ombudsman is accountable to parliament, not the prime minister, the public inquiry is initiated by the prime minister through the Inquiries Act, a different legal instrument that is governed by different rules.

He argues that the ombudsman “cannot be considered to be an Officer of Parliament when chairing the Board of Inquiry”.

Said Pullicino also warns about the possible repercussions of involving the ombudsman in an inquiry of this sort.

“There are obviously risks of institutional conflicts and possible creation of dangerous precedents that one should be aware of and that should be averted.”

Therese Comodini Cachia, the opposition MP and consititional lawyer who raised the issue in the first place, holds a similar view, arguing that by being involved in the public inquiry, both the auditor general and the ombudsman risk “seriously jeopardising their independence”.

On the other hand, another constitutional expert who preferred to remain unnamed held a different view, saying that the law does not preclude either the auditor general or the ombudsman from forming part of the inquiry board.

Has this ever happened before?

This is not the first time that the ombudsman and the auditor general were appointed to a similar board by a prime minister. In 2014, then-Prime Minister Joseph Muscat set up a board to provide recommendations on how the honoraria of MPs were to be awarded.

That board was composed of the Ombudsman Joseph Said Pullicino, Auditor General Anthony Mifsud and the then-chief electoral commissioner.

Said Pullicino argues that the two cases are different, as the previous board was “not required to investigate any action or inaction of the public administration”, but rather to recommend a remuneration mechanism for MPs.

Verdict

The law prohibits the auditor general from holding any other office and only allows the ombudsman to take on another role if it doesn’t impact their impartiality.

Constitutional experts have different views on whether forming part of the public inquiry board would constitute a conflict. The office holders themselves argue that this will not be the case.