Word-of-the-year titles are hardly the obvious place to start when talking about misinformation, but they sometimes offer a useful glimpse into what captured people’s imaginations throughout a year.

Hot off the heels of Trump’s election as US President, ‘fake news’ was named Collins Dictionary word of the year in 2017.

A year earlier, with the Brexit referendum and US election campaigns in full swing, the Oxford Dictionary had gone for ‘post-truth’.

In 2018, Dictionary.com opted for ‘misinformation’, pointing to its almost uncontrollable spread through social media.

This year’s picks included Merriam-Webster’s ‘authentic’ and the Cambridge Dictionary’s ‘hallucinate’, a term which refers to chatbots’ infuriating habit of making things up.

Collins Dictionary, cutting to the chase, simply opted for ‘AI’.

2023 is likely to be remembered as the year in which the sands of misinformation narratives shifted more prominently from man to machine, at least in people’s imaginations.

The newfound popularity of generative artificial intelligence, from ChatGPT to image generators such as DALL-E and Midjourney, caused many to fear a deluge of AI-generated content being used to maliciously dupe people.

An early, harmless warning came early in the year with the ‘dope pope’, an AI-generated image of Pope Francis decked in a white Balenciaga puffer jacket, which went viral after being posted on Reddit.

Other similar images soon followed.

Just a few weeks later, the internet was flooded with images of Donald Trump being chased and arrested by police. While Trump’s arrest would soon become reality later in the year, it was far less dramatic than the fabricated pictures suggested.

Things took a darker turn over the summer in the Spanish town of Almendralejo, where a group of local boys were arrested for creating and sharing pornographic deepfake images of over 20 girls between the ages of 11 and 17.

The malicious use of deepfakes also reached Malta over the summer, when Times of Malta revealed that scammers were using AI-generated deepfakes as part of an elaborate cryptocurrency scam.

AI-generated videos, audio and images have also been used to muddy political waters.

In one widely shared fake video, French President Emmanuel Macron was seen announcing his resignation. Meanwhile, in the run-up to the country’s national elections, an AI-generated voice recording of Slovakia’s Progressive Party leader Michal Šimečka, supposedly talking about the party’s plan to increase alcohol prices, was created and shared online.

But misinformation in 2023 was about more than just AI.

Politics, scams and pseudoscience shape Malta’s misinformation landscape

Locally, misinformation narratives were often dominated by the political issues of the day.

Early in the year, the court’s decision to scrap the fraudulent hospitals concession, a deal which gave private healthcare companies control over three public hospitals, led to several misleading claims about the deal from across the political spectrum.

As the pressure mounted on the government to hold a public inquiry into the death of Jean Paul Sofia, a young man who was buried under the rubble of a collapsed building in December 2022, several government actors, including Prime Minister Robert Abela and Justice Minister Jonathan Attard repeated the false claim that a public inquiry serves the same purpose as a magisterial inquiry.

The year was also characterised by unfounded claims about Malta’s population. A series of social media posts throughout the year falsely claimed that foreigners are now outnumbering Maltese citizens, prompting commenters to post anti-foreigner tropes. Opposition leader Bernard Grech later jumped into the fray, falsely saying that Malta’s population had almost doubled over the past decade.

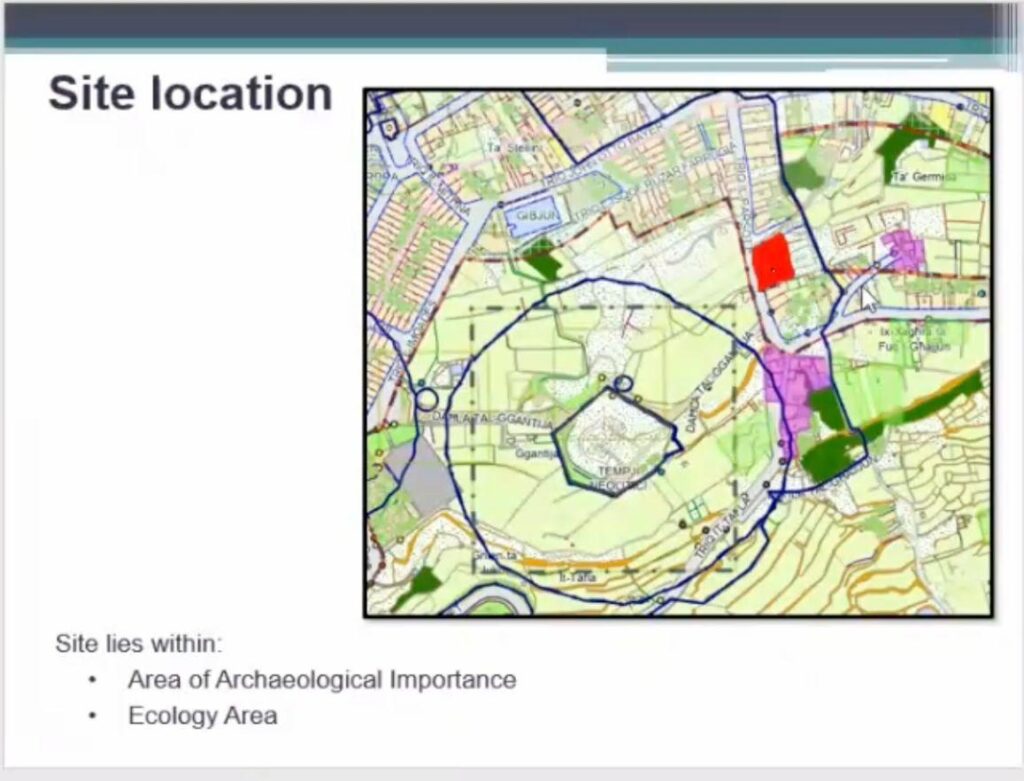

Misinformation was also rife across discussions of several major construction projects throughout the year. A proposed apartment block just metres from the historic Ġgantija temples in Gozo was approved on the false premise that the site lay outside the UNESCO buffer zone established for the site. Earlier in the year, developers and environmental groups bickered over whether or not the new hotel and bungalows on Comino would be larger than the existing buildings.

Scammers became far more adept at working current affairs into their scams throughout 2023. Gone are the scam posts of old, with their garbled syntax and comical typos, now replaced by almost picture-perfect spoof websites riffing on issues currently in the public eye.

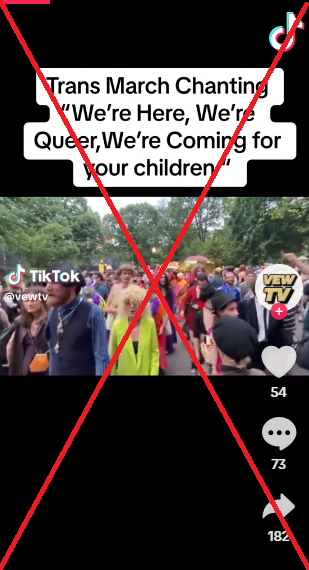

Misinformation narratives surrounding major global events also worked their way to Malta, whether it was bogus pseudoscientific claims about the earthquakes in Turkey and Syria at the beginning of the year or several misleading memes and videos about the LGBTQ+ community shared throughout EuroPride in September.

Unprecedented levels of disinformation in Israel-Hamas war

However, nothing quite matched the wave of disinformation that was spread across social media following the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war in early October. While 2022 was characterised by disinformation about the Ukraine war, disinformation experts say that this took on unprecedented levels throughout the ongoing violence in the Middle East.

Several examples of this disinformation also came to Malta’s shores, particularly in the early weeks after fighting broke out. It came in many shapes and sizes; videogame footage used to emulate real attacks, fake social media accounts claiming to be journalists or eyewitnesses, manipulated audio and video recordings and unverified accounts about attacks and casualties.

While none of these techniques were new, the sheer volume of disinformation surrounding the war overwhelmed fact-checkers and media houses around the world.

What does 2024 have in store?

As the new year rolls in, disinformation experts are bracing themselves for what they expect to be an onslaught of disinformation throughout 2024.

Many believe that the malicious use of AI during electoral campaigns held across Europe this year was only dry run for next year, when European Parliament and US elections are set to be held and AI’s potential to supercharge political propaganda could come to the fore.

Meanwhile, experts say they also expect to see more false claims about electoral manipulation, including allegations of voter fraud and rigged elections, similar to the playbook adopted following the US elections in 2020.

The Times of Malta fact-checking service forms part of the Mediterranean Digital Media Observatory (MedDMO) and the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), an independent observatory with hubs across all 27 EU member states that is funded by the EU’s Digital Europe programme. Fact-checks are based on our code of principles.

Let us know what you would like us to fact-check, understand our ratings system or see our answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the service.