The Maltese government launched a public consultation into what it is calling “assisted voluntary euthanasia” on 7 May, proposing that persons suffering from a terminal illness may choose to end their life under certain strict conditions.

Unsurprisingly, the news sparked a range of views, ranging from those adamantly opposed to the idea to others who felt the proposals did not go far enough, as well as several contrasting claims over how what Malta is proposing compares to other models adopted outside Malta’s shores.

In launching the consultation, parliamentary secretary Rebecca Buttigieg said that experts had looked at several models across the world in drafting the proposals.

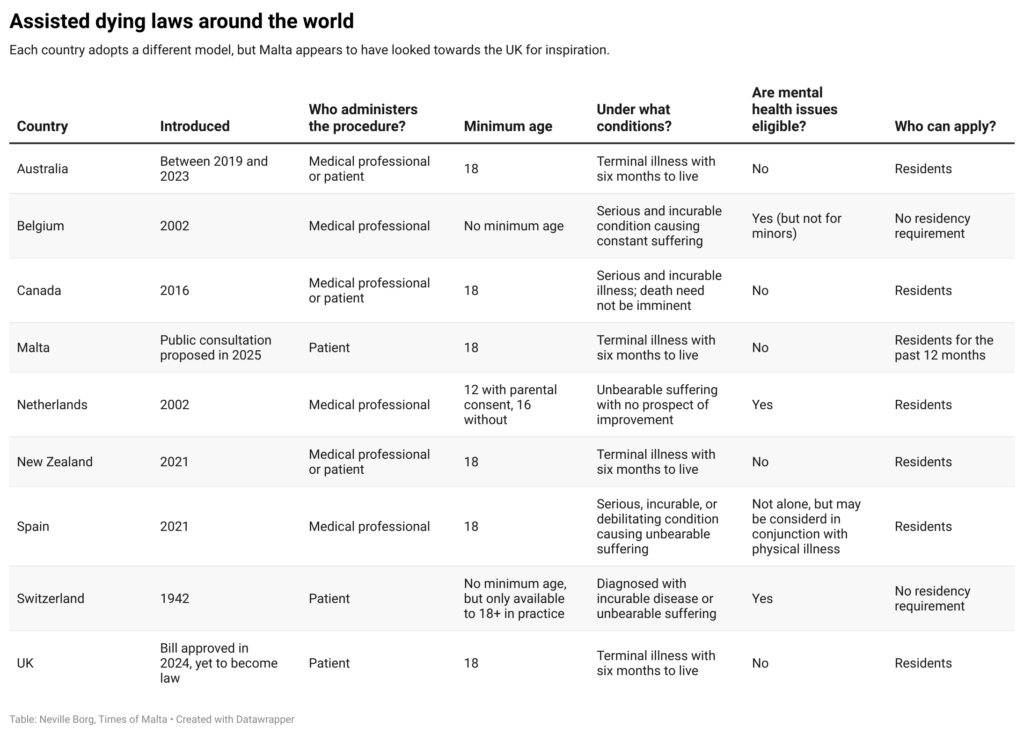

Over a dozen countries have introduced some form of legislation to allow euthanasia or assisted dying, including several EU member states. However, no two laws are identical, with each model adopting different legal and ethical parameters.

“We completely ignored liberal models,” Buttigieg said during an episode of Times Talk, insisting that there are certain red lines that Malta will not cross.

What is Malta proposing?

The model proposed in Malta’s public consultation adopts fairly strict eligibility criteria for anyone looking to end their life.

For a start, anyone under the age of 18 is automatically excluded, as is anyone who has not been diagnosed with a terminal illness.

Even if they do have a terminal illness, they must have first exhausted all available treatments, with a doctor certifying that they are expected to die naturally over the next six months.

Patients cannot request the procedure solely due to a disability, mental health issue, or age-related condition such as dementia.

Several other measures intended to ensure that the patient is reaching the decision out of their own free will are also being proposed, with the patient at liberty to change their mind at any point of the process.

And ultimately, despite the presence of a medical professional, it will be the patient who will carry out the procedure.

This suggests Malta is proposing a model closer to assisted dying, rather than euthanasia, where third parties administer the procedure.

How does assisted dying work in other countries?

Arguably, the country most synonymous with assisted dying is Switzerland, the first country to enshrine the right to die into law over 80 years ago.

Switzerland has among the more liberal assisted dying laws in the world, offering the procedure to people who are not necessarily terminally ill.

While the finer details tend to vary from one region (or canton) to another, Switzerland offers assisted dying procedures to any adult who is suffering from an incurable disease or plagued by unbearable suffering, even if this is caused by old age.

And Switzerland also allows people to apply for the procedure citing mental health reasons, although these cases tend to be very rare and highly scrutinised, making them the exception to the rule.

Several other European countries have adopted similar approaches in recent years, albeit each with some differences.

In Belgium, the procedure is available to minors in certain cases, as well as to people who are suffering from severe psychological distress or mental health issues, including chronic depression, PTSD and personality disorders.

In Spain, assisted dying or euthanasia is available to adults suffering from a debilitating disease, with patients also able to cite mental health issues as a contributing factor.

And the Dutch model says that anybody experiencing unbearable physical or psychological suffering with no prospect of improvement can apply. Dutch law allows children as young as 12 to apply, as long as they have parental consent.

But unlike Switzerland, which notoriously offers the procedure to anyone travelling to its alpine heartland, many of these countries require applicants to be residents first.

Even across the ocean, governments are increasingly legislating for assisted dying.

Canada introduced legislation permitting assisted dying and euthanasia for the terminally ill in 2016.

Over the years, this was expanded to include people with chronic and incurable (but not necessarily terminal) illness, with mental illness also scheduled for inclusion by 2027.

Because of this, Canada is frequently cited by critics of assisted dying as an example of a slippery slope in which euthanasia advocates gradually chipped away at an initially restrictive law.

Meanwhile, assisted dying is permitted across several US states, each of them having slightly different safeguards and protocols. But to date, no US state offers euthanasia, in which the procedure is administered by a third party.

Maltese model similar to UK’s proposed bill

Given the long-standing British influence on Malta, it comes as no surprise to find that Malta’s model appears to closely mirror the bill that was approved by UK parliamentarians last November.

Like Malta, the British bill proposes that assisted dying be available to adults who are terminally ill with a prognosis of under six months left to live.

Mental health factors cannot be taken into account, with the life-ending medication being self-administered by the patient themselves, after it has been prescribed and approved by a doctor.

And the safeguards in place to ensure that the patient is reaching the decision of their own free will, without any external pressure, are also similar to those proposed in Malta, such as a cooling-off period (14 days in the UK’s case, compared to Malta’s seven) and providing several levels of review.

Malta’s model also shares elements with the legislation introduced in New Zealand in 2021, a year after two-thirds of residents voted to legalise assisted dying in a referendum.

Like Malta, New Zealand law says that the procedure can only be administered to someone with a terminal illness with under six months to live.

New Zealand, in turn, borrowed much of its framework from neighbouring Australia, although the latter extends the prognosis to 12 months in cases of neurodegenerative conditions.