In the midst of the protracted public back-and-forth between the government and investment consortium MIDI throughout the summer months, Robert Abela challenged journalists to compare the original plans for Tigné Point with what eventually transpired

The “exaggerated development” at Tigné Point “was not what was approved in the development brief,” Abela said.

“If we look at how the development was meant to be according to the public call and compare it to the physical development today, there is no resemblance,” he added, pinning the blame on successive PN governments for allowing the developers to stray from the original plans.

MIDI had been set up two decades ago to successfully bid for a public concession to develop two prime location sites. Although one of the planned developments, at the seafront site of Tigné Point, was completed, works at the other site, Manoel Island, never took off. In June, amidst mounting public pressure, the government announced that it would be taking legal action against the consortium over the delays. Discussions between MIDI and the government to rescind the concession altogether are ongoing.

Reading through the terms of the public call today shows that while Abela is right to say that today’s Tigné Point bears little resemblance to what was originally promised, the changes to the project were all given the blessing of public authorities within subsequent administrations, including those of Abela’s own Labour party, over the past 30 years.

What is the development brief?

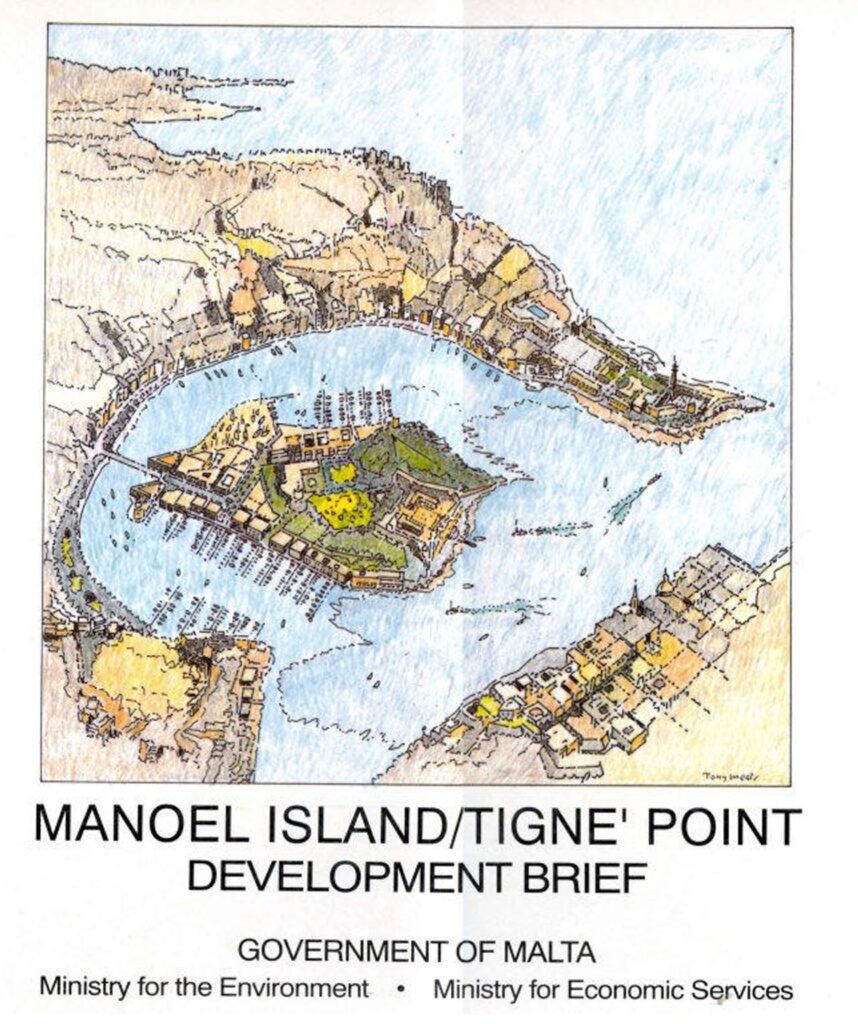

Abela was referring to a development brief published in 1992 by the government of the day, calling on business leaders to submit their bids to develop both Tigné Point and Manoel Island.

The brief outlined what sort of development should take place on the sites, providing prospective bidders with detailed guidance on how to transform the sites.

Both Tigné and Manoel Island were in a state of neglect at the time.

Tigné had become home to Malta’s ramshackle DIY music scene, with misfit teens shuffling into the barracks and transforming them into rehearsal spaces for their bands. Meanwhile, Manoel Island was considered a no-go area at night, mostly frequented by drug users and prostitutes.

An initial call for interest attracted significant local and international interest. A total of 54 companies expressed interest in the project, with 18 of them formally submitting qualifying offers. These were then whittled down to a shortlist of nine, each of them given a copy of the development brief and told to present their proposals.

By Christmas time 1993, the bid was awarded to a Maltese/Italian consortium featuring MIDI, which would later take over the project entirely.

The development was “expected to take between five and 10 years to complete,” according to news reports of the day. By mid-1994, the land’s lease would be signed and MIDI would have submitted their outline development proposal to the Planning Authority, the government promised.

Things would turn out to be more complicated than that.

It would be several years of negotiations before the deal was finalised and the concession agreement finally signed in June 2000. And while the project’s outline development permit would indeed be submitted in 1994, it would take until 1999 to be green-lighted by authorities.

And now, more than a quarter of a century (and countless revised planning applications) later, one half of the agreement appears to be on the brink of collapse, with discussions ongoing to return Manoel Island to the government.

However, works on the other half, Tigné Point, have been almost entirely completed, giving us a glimpse of how the project changed from how it was originally conceived back in distant 1992.

What was Tigné Point meant to be?

Malta’s burgeoning tourism industry was at the forefront of the development brief, with the document saying the sites were to be developed for “tourist, yachting and commercial purposes”.

While the yachting component would be mostly restricted to Manoel Island (in 1991 the government said it wanted to turn Marsamxett harbour into the “biggest yacht marina in the Mediterranean”), Tigné Point was earmarked for “tourist related facilities and accommodation”.

In practice, Tigné Point was to become home to a 200-bedroom five-star hotel which would “wrap-around” Fort Tigné, together with another two smaller 80-bedroom hotels.

The brief lists several other potential amenities to be built on the site, from an exhibition centre to some sort of “crafts village, studios or small professional offices”.

However Tigné Point “should not be a major commercial centre for either shops or offices,” the brief insisted, arguing that other sites are more appropriate for shopping centres.

How much was to be built?

The brief doesn’t quite outline a total built footprint for the entirety of Tigné Point, instead setting a maximum level for the different types of development across the site.

According to the brief, Tigné Point would hold up to 12,000 square metres of retail space, 20,000 square metres of office space and 300 residential units, together with 3,200 square metres worth of restaurants, cafes and bars.

“These maximum levels do not need to be achieved,” the brief notes, adding that they depend on improvements to the area’s transport network.”

The brief adopts a similar approach when discussing building heights.

The project’s main building, the 200-bedroom hotel, would be two or three floors, the brief said.

A business centre and residential units in one zone of the site would rise slightly higher, reaching four floors.

Meanwhile, another zone would be home to the project’s highest buildings, with shopping facilities, residential apartments and offices rising to a height of six floors.

Ultimately, the brief said, new buildings would have to be “of an appropriate scale, proportion and bulk”.

“The mass and scale of new development should not visually dominate the older buildings,” it added, referring particularly to Fort Tigné.

How did plans change?

The development brief’s plans quickly went out the window.

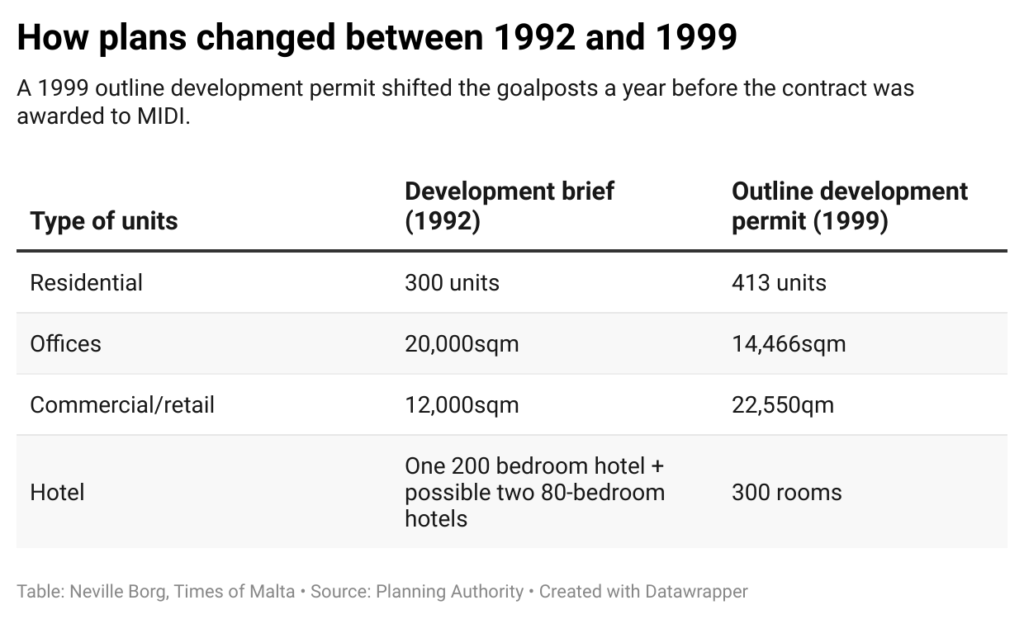

By the time the concession agreement was signed and the land handed over to MIDI in 2000, the project’s parameters had changed, with the planning authority having approved new plans in the 1999 outline development permit.

The permit was attached to the concession agreement, meaning that MIDI was effectively duty-bound to follow the revised plans, not the original development brief.

The 1999 permit shows how the number of residential units grew from the 300 listed in the brief to 413. Likewise, commercial space ballooned from 15,200sqm to 22,550sqm.

On the other hand, the planned office space shrank from 20,000sqm to just under 15,000sqm.

The hotel, at one time the heart of the project, also changed. What was initially a 200-bedroom hotel with the possibility of a further two 80-bedroom hotels became a single 300-bedroom hotel spanning 19,500sqm.

Excluding its several underground parking areas, the 1999 plans show that the project would span a total of 132,055sqm.

The outline development permit also completely changed the area’s building heights. What was originally a maximum of six floors rose to a possible 23 floors, with the permit approving “the principle of the tower block”.

What was eventually built?

Plans changed again after the project contract was awarded.

The most drastic of the changes came when, shortly after initial works kicked off in the early 2000s, the Planning Authority issued instructions for the 19th-Century Garden Battery, a site originally earmarked for development, to be preserved.

An overhaul of the design followed, with a revised masterplan shifting part of the area’s built footprint into a series of high-rise towers instead.

In 2019, the Planning Authority also agreed to shift 8,000sqm of development initially earmarked for Manoel Island to Tigné Point, allowing the developers to increase the site’s built density.

Planning Authority reports reveal that, when all this is taken into consideration, the project’s built footprint is marginally larger than set out in the initial 1999 outline development permit (plus the additional 8,000sqm shifted from Manoel Island), with some 205sqm of built floor space more than planned.

But while floor space may be roughly similar, the project itself would be unrecognisable to anyone taking the 1992 development brief as a blueprint.

Rather than hotels and tourist amenities no higher than six floors, a series of residential blocks, some rising to 17 floors, now dominate the skyline, towering over the newly-restored Fort Tigné.

Meanwhile, the restored Garden Battery and central square, a site once deemed unsuitable for a major commercial centre, lead to The Point shopping mall which describes itself as “Malta’s largest retail centre” and a “mecca” for shoppers.

Today, Tigné Point today stands as a striking example of how a large-scale development can evolve far beyond its original scope, with the approval of successive governments, as priorities change and logistical issues emerge over the years.

The Times of Malta fact-checking service forms part of the Mediterranean Digital Media Observatory (MedDMO) and the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), an independent observatory with hubs across all 27 EU member states that is funded by the EU’s Digital Europe programme. Fact-checks are based on our code of principles.

Let us know what you would like us to fact-check, understand our ratings system or see our answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the service.