Recent weeks have seen a series of police searches across several Maltese towns in which migrants were found to be living without the necessary documentation.

While news of these searches was welcomed by some, others viewed the police’s actions as heavy-handed and possibly racially motivated. Others still have claimed that such searches are illegal and constitute a breach of human rights.

Several readers, sparked by the online debate over whether or not these searches are legitimate. wrote to Times of Malta questioning the legality of police searches on properties and asking whether police have the authority to carry out stop and searches without a search warrant.

This is not the first time that concerns over racial profiling emerged.

In 2018, police denied racial profiling during routine immigration checks after reports that plainclothes officers were stopping people believed to be migrants to ask for their residence documents.

Earlier still, in 2017, a man spoke of his humiliation at being approached by police officers in the southern town of Birżebbuġa, whilst white foreigners who were also in the area were ignored.

Police action is governed by Malta’s criminal code, which spells out what police are allowed to do and what is forbidden.

Can police carry out a stop and search without a warrant?

Yes, in some cases, although there are exceptions.

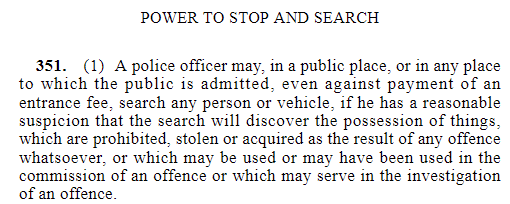

One section of the code, handily titled ‘Power to stop and search’, says that police are allowed to search any person or vehicle without needing to have a warrant, as long as there is “reasonable suspicion” that the search will find illicit material or evidence of a crime.

The code, however, stops short of describing what constitutes “reasonable suspicion”, giving police a free hand to interpret this as they see fit.

When asked by Times of Malta to define “reasonable suspicion”, police skirted around the issue, simply saying that they are “duty-bound to ensure that all persons are residing in Malta legally” and carry out verifications “on a routine basis”, together with other entities.

Nevertheless, there are instances in which even reasonable suspicion does not suffice.

For instance, police officers on patrol cannot break into an unattended car on a whim, even if they suspect that there may be illicit material stored inside. They would first need to get a warrant signed off by a high-ranking police official.

Meanwhile, a plainclothes police officer cannot simply stop and search a person but needs to first identify themselves by producing their police ID card.

On the other hand, Malta’s Identity Documents Act does away with the concept of reasonable suspicion entirely, simply saying that everybody must produce their identity document “on demand” when asked to do so by “any lawful authority”.

This suggests that while the police are at liberty to ask for a person’s identity or resident documentation at any time, there needs to be a level of suspicion for a full search to be carried out.

Are road checks allowed?

Road checks work roughly in the same way as stop and searches.

Police need to have “reasonable grounds” on which to believe that a road check will lead them to discover an illegality. Approval for the road check needs to be signed off by a senior police official.

Again, the law does not specify what reasonable grounds mean in practice.

On the other hand, police can stop and search any vehicle during the road check, regardless of whether or not they suspect an individual vehicle or driver of any wrongdoing.

What about property searches?

The law is a little more stringent when it comes to searching a person’s home or property.

In this case, police need to have a search warrant signed off by a magistrate, not just a senior police official, before starting a search.

Sources told Times of Malta that it is not unheard of for magistrates to refuse to issue a search warrant, with the courts needing to be convinced that the action that will be taken is justified.

As always, there are exceptions.

Police can act immediately, without waiting for a warrant, if they believe that there is “imminent danger” that a suspect may escape or if they believe that the search will capture a suspect who is on the lam.

They can also forego the need for a warrant if they spot a person inside the property in the act of committing a crime or if they believe that intervening immediately will prevent a crime.

Did migrant housing searches need a warrant?

In principle, yes. The law does not distinguish between searches for criminal activity and checks for residential documents or immigration checks.

The police did not confirm whether the searches on migrant accommodation over recent weeks were covered by a magistrate’s warrant, simply saying that searches are carried out in line with the Immigration Act and Malta’s Criminal Code.

Police must foster ‘public perception’

In comments to Times of Malta, Aditus director and lawyer Neil Falzon stressed that police power “must be exercised responsibly and respectfully”, saying that targeting people based on features such as skin colour and sexual orientation, or even targeting specific areas in Malta, “could be discriminatory”.

What’s more, Falzon argues, the police play a crucial role in fostering public perception, with actions in which persons are accompanied by Detention Services fuelling “the incorrect public perception that Malta is rampant with irregularly staying persons who must be locked up”.

Falzon says that police activities “should not create a sense of public insecurity or personal embarrassment” and the way activities are communicated must steer clear of “misleading messaging to gain political mileage”.

Police ethics

The police’s code of ethics, last updated in 2020, says that police officers must be “guided by the principles of impartiality and non-discrimination” while carrying out their duties. It goes on to instruct officers to treat “all minority communities” with respect and give vulnerable groups “due consideration”.

A police spokesperson told Times of Malta that the force recently worked with the Human Rights Directorate to develop internal standard operating procedures on the wellbeing of detainees and was recognised by the Equality Commission as an inclusive organisation.

“The Malta Police Force is committed to ensuring that the Maltese people live securely in their country as a community while cooperating with other ethnic groups of people.”

Verdict

Searches and requests for identity documentation are legal but may require approval by senior police officers or magistrates in some cases.

Nonetheless, concerns over racial profiling persist, with experts saying that police must be careful to act with impartiality and not fuel a misleading public perception.

The Times of Malta fact-checking service forms part of the Mediterranean Digital Media Observatory (MedDMO) and the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), an independent observatory with hubs across all 27 EU member states that is funded by the EU’s Digital Europe programme. Fact-checks are based on our code of principles.

Let us know what you would like us to fact-check, understand our ratings system or see our answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the service.