Claim: A proposed reform to planning laws only allows illegal developments to be regularised if a small part of the development is illegal

Verdict: The proposed laws allow people to apply to have an entire illegal development regularised, not just a small part of it.

A fiery debate between Michael Stivala, head of Malta’s largest construction lobby and activist Wayne Flask was characterised by contrasting claims over what a controversial reform to Malta’s planning laws say.

A series of new bills and legal notices presented by the government earlier in summer promise to overhaul Malta’s planning laws, introducing new procedures through which objections to developments can be appealed.

Controversially, the bills also say that illegal developments, even those outside development zones, can be regularised through the stroke of a pen, as long as owners pay a substantial fine.

Critics taken to the streets to call on the reforms to be withdrawn and sent back to the drawing board, arguing the new rules steamroll over citizens’ rights and will lead to unfettered construction.

The reform was at the heart of the debate hosted by Times of Malta and aired on Friday October 3, which pitted Stivala, the head of the Malta Development Association, against one the Flask, an outspoken voice against overconstruction.

Towards the end of the debate, the pair found themselves at odds over whether the proposed rules will allow applicants to regularise a property that is entirely in breach of Malta’s planning laws, or whether only part of a property can be regularised.

Flask argued that this will impact anybody, from people with a minor infringement in their property to others who built an entirely illegal property on protected land.

“This is rewarding people who broke the law,” Flask argued, adding that regularisation will apply to buildings built as recently as last year.

“If I have an illegal sheep farm, why should it become legal?” Flask asked. “If I have an illegal home, why should it be made legal, only for someone years later to turn it into a hotel?”

“It can’t be a whole illegal building to be regularised,” Stivala retorted, adding that “there are percentages, it’s only for those who have a small percentage of their property which is illegal, it can’t be a whole building”.

What does the proposed law say?

The answer to Flask and Stivala’s dispute lies in a series of legal notices published as part of a broader public consultation on the planning reform in early August.

The consultation presents three proposed legal notices, each outlining how authorities would be blessing illegal developments in different areas, if the reform was to go through.

One of these legal notices tackles illegal developments within development zones, while the second speaks of buildings in breach of planning laws that are outside development zones.

A third legal notices describes how the owner of an illegal property can apply for a concession, rather than for it to be fully regularised.

Unlike full regularisation, which means that the illegal property is brought in line with the law, a concession means that the property would still be considered illegal, but authorities would not take action against the illegality.

In all three cases, the proposed new rules do not place any limit on whether the owner of an illegality can apply to have a full building blessed by authorities, or just part of one.

However, the bills add that, in certain cases, if the illegal portion of a development is less than 30% of the building’s total footprint, the owner will receive a 50% discount on the fees owed to have the property regularised.

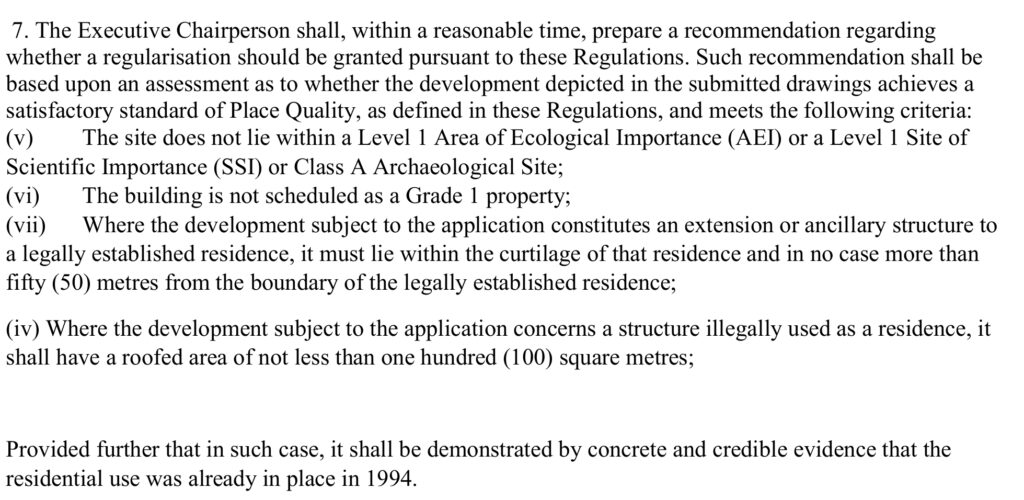

The laws also place certain eligibility criteria. The illegal development cannot be within specific protected areas (such as areas of archaeological importance, for instance), nor can it be scheduled as a Grade 1 property.

The development will also need to achieve a “satisfactory standard of place quality,” the rules say, describing this as the integration of a building with its surrounding environment, “with particular emphasis on visual harmony and good neighbourliness”.

The rules do not say how this will be assessed.

Concession until 2024, not regularisation

During the debate, both Flask and Stivala said that illegal developments built as recently as 2024 will be eligible for the new regularization scheme.

This is not the case, with the pair mistakenly referring to the cutoff date for a similar concession scheme.

The proposed rules say that an illegal development in a area earmarked as being an outside development zone will have to been built before 1994, with applicants required to present proof that the development existed by 1994 in order for their application to be considered.

Meanwhile, the cutoff date for illegal developments within development zones will be 2016 with anyone wishing to have their illegal development blessed needing to show evidence of its existence by this point.

However, while illegal developments built between 2016 and 2024 will not be eligible for regularization, they would be eligible for a concession, effectively removing the risk of any enforcement action being taken against the illegality.

Verdict:

A proposed reform to Malta’s planning laws will allow owners of illegal developments to regularize their property.

The proposed rules do not place any limit on the size of the irregularity to be regularised, effectively allowing applicants to apply for an entire illegal property to be brought in line with the law.

However, applicants will have to show that an illegal development outside a development zone existed by 1994, while those within development zones will have a cutoff date of 2016.

Owners of illegal developments built after this date will be eligible for a concession, effectively preventing any enforcement action against them, but not full regularization.