Prime Minister Robert Abela told party faithful on Sunday January 14 that while inflation on many items is going down, inflation on food is bucking this trend, with shoppers seeing increasingly high prices on supermarket shelves.

Abela was defending the government’s move to push supermarket owners and importers to reduce the prices of staple grocery products by 15%.

Earlier in the day, the Malta Chamber of Commerce had criticised the move, saying that inflation in food prices was similar to what was registered in other European countries. The price increases, the Chamber argued, were mostly driven by rising logistical costs and spiralling wage costs.

Speaking on Sunday, Abela said that many people are concerned about the rise in food prices that they experience in their weekly shop.

“This is what statistics are showing, and statistics don’t lie”, Abela said. “While inflation on many items is going down, you have a different reality when it comes to food prices. Not only is inflation not decreasing but there is an upward movement in prices”.

Several readers wrote to Times of Malta to verify whether or not this is correct and whether food inflation is increasing, unlike most other types of inflation.

How is inflation measured?

If we want to get to the bottom of this we need to first understand how inflation is measured.

In practice, researchers compile a basket of goods and services consumed by households (food, energy costs, fuel, clothing and so forth), and then compare its total cost to that of the same basket in previous months or years. The increase in the price of the basket is the overall inflation rate.

But, rather confusingly, two measures of inflation are often used.

One is the annual inflation rate (Malta’s most recent score is 3.9%, registered in November), which measures the difference between the current month and the same month the previous year. So, in effect, Malta’s inflation in November 2023 was 3.9% higher than it was in November 2022.

This measure gives a good indication of rising prices but tends to be quite sensitive to drastic one-off changes. If, for example, the price of a particular group of items suddenly spikes because of a temporary shortage, then the inflation rate is likely to appear to be disproportionately high.

The other measure, known as the 12-month moving average is more stable, comparing the average inflation rate over the past 12 months to that over the previous 12 months. This means that it’s less likely to be affected by dramatic rises or dips in prices. Malta’s current 12-month moving average is 5.9%.

Aside from overall inflation, both measures also look into inflation across different groups of items or services, such as food, transport, healthcare and clothing, amongst several others.

Things quickly get very complicated, with different items having a different weight towards the overall rate of inflation. So, for instance, coffee has a weight of just 0.4% (criminally low, if you ask me) while petrol has a weight over ten times greater at 4.6%, meaning that a change in the price of petrol will have ten times the impact when it comes to measuring overall inflation, compared to a change in the price of coffee.

How is food inflation doing?

Not great, but better than it was.

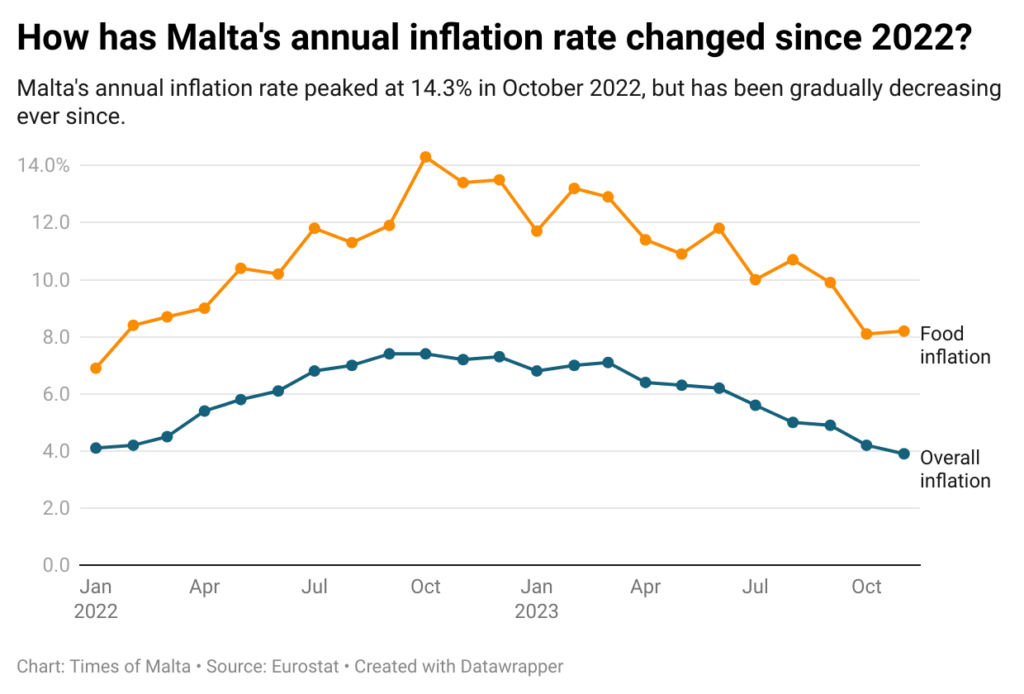

Malta’s annual food inflation rate has been over 10% ever since May 2022, peaking at 14.3% that October, before finally inching downwards into single digits last September.

In October and November 2023, the rate remained stable, at just over 8%.

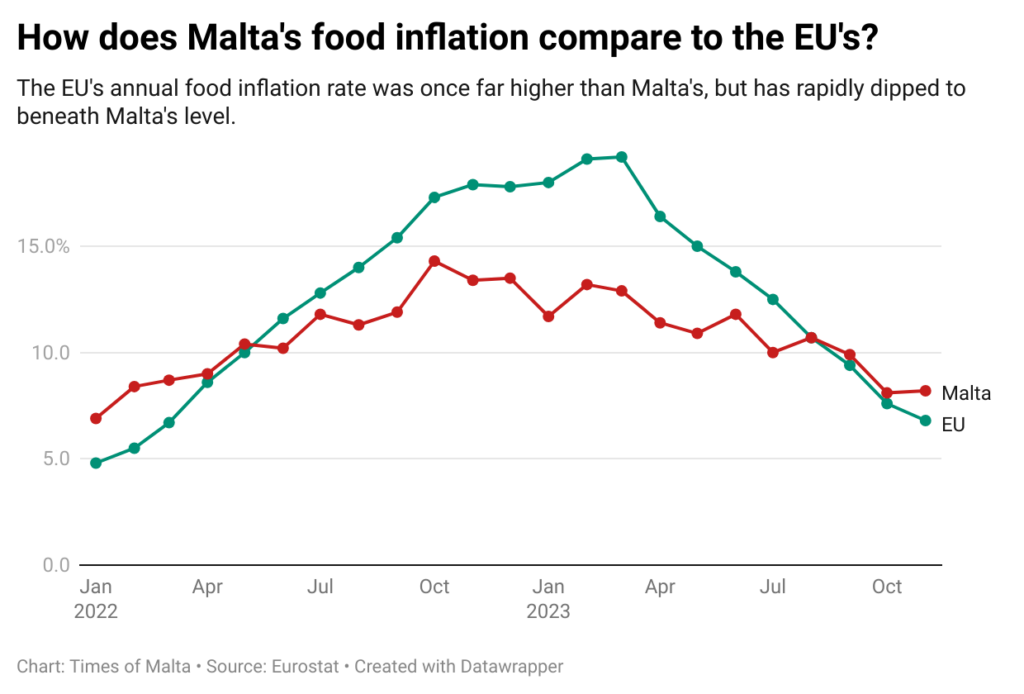

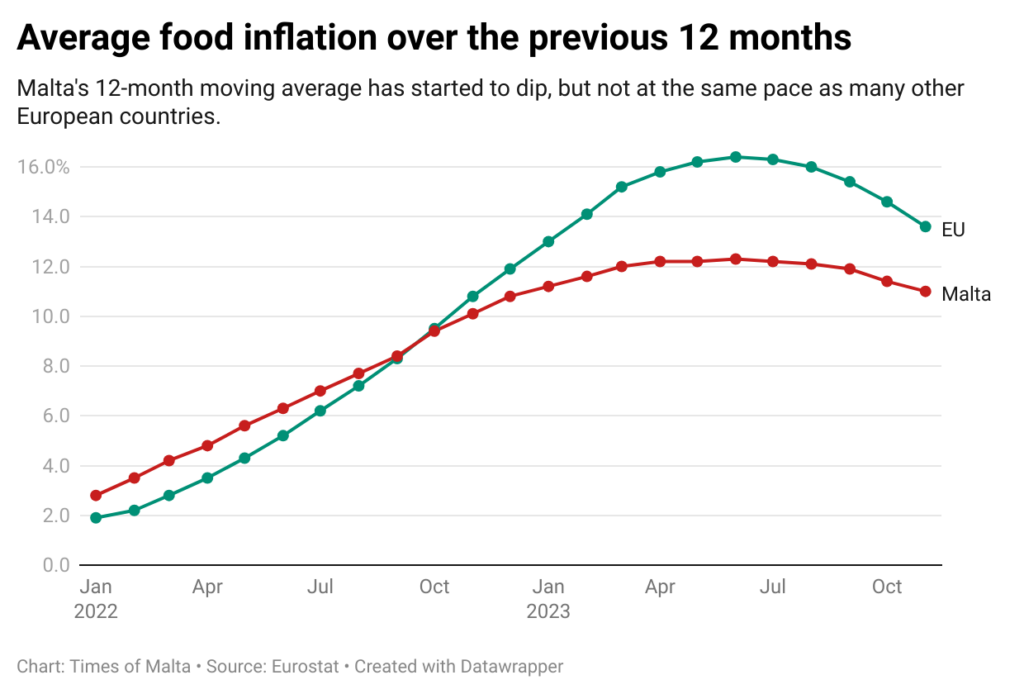

A similar trend can be seen across Europe, although food inflation in Malta seems to be decreasing at a noticeably slower rate, compared to the rest of the EU.

However, food inflation in the EU was higher than it ever was in Malta, hitting 19.2% in March 2023 and remaining higher than Malta’s until August, eventually dipping below Malta’s level.

The most recent data shows that the EU’s annual food inflation rate is 6.8%, compared to Malta’s 8.2%.

Malta’s food inflation also appears to be on the slide if we look at the 12-month moving average, going from a high of 12.3% last June to 11% in November.

Meanwhile, the EU’s average has also dipped from 16.4% to 13.6% during the same period.

Is inflation in other sectors dropping too?

Yes, at least in most cases.

Inflation on clothing and footwear has dipped from a 12-month average of over 4% at the beginning of 2023 to just under 3% by the end of the year, while that of transport has more than halved, going from 5% to 2.1%.

Even in cases where inflation remains high, such as the housing sector’s 7.8%, this nonetheless marks a dip from the over 9% registered a year ago.

So if inflation goes down, prices go down, right?

Not quite.

A drop in inflation simply means that prices are increasing at a slower rate, not that prices are going down.

Price decreases following a dip in inflation are, unfortunately, very rare. Local economists frequently point to the phenomenon of ‘price stickiness’, where high prices tend to stick around long after the causes of those high prices have gone away.

This, they say, could be driven by a lack of competition and the risk of businesses reaching tacit agreements to set pricing.

Finance Minister Clyde Caruana made a similar argument last October, telling Times of Malta that Malta’s markets are largely “made up of cartels”.

So just because there is a decrease in food inflation, shoppers are unlikely to suddenly see cheaper prices on supermarket shelves.

Verdict

Food inflation is on the decrease across Europe as well as in Malta, with several inflation measures showing that this has now dipped significantly compared to some months ago.

Nonetheless, food inflation in Malta appears to be decreasing at a slower rate than in most other European countries.

But this doesn’t mean that shoppers will see cheaper prices on supermarket stalls. A decrease in inflation simply means that prices are increasing at a slower rate, not that prices are going down.

So while Abela may be correct when saying that consumer’s food prices are increasing, it is incorrect to say that food inflation is not decreasing.

The Times of Malta fact-checking service forms part of the Mediterranean Digital Media Observatory (MedDMO) and the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), an independent observatory with hubs across all 27 EU member states that is funded by the EU’s Digital Europe programme. Fact-checks are based on our code of principles.

Let us know what you would like us to fact-check, understand our ratings system or see our answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the service.