Responding to questions about calls for a public inquiry into the death of Jean Paul Sofia, Justice Minister Jonathan Attard claimed that a public inquiry “will not reveal anything different” from a magisterial inquiry.

The 20-year-old was killed in a building collapse at a construction site in Corradino last December. Five other workers were injured in the incident.

A magisterial inquiry headed by Magistrate Marse-Ann Farrugia was immediately launched, however, the opposition has repeatedly called for a public inquiry into Sofia’s death. Sofia’s mother, Isabelle Bonnici, is also urging MPs to call for a public inquiry into the death of her son.

Attard’s claim echoes similar statements made by Prime Minister Robert Abela, who has argued that a magisterial inquiry “has all the tools and resources to establish who was responsible and identify failures” for Sofia’s death.

Abela has repeatedly called for the magisterial inquiry to be concluded as quickly as possible, even writing to Chief Justice Mark Chetcuti to complain about the “unacceptable delay” in the inquiry.

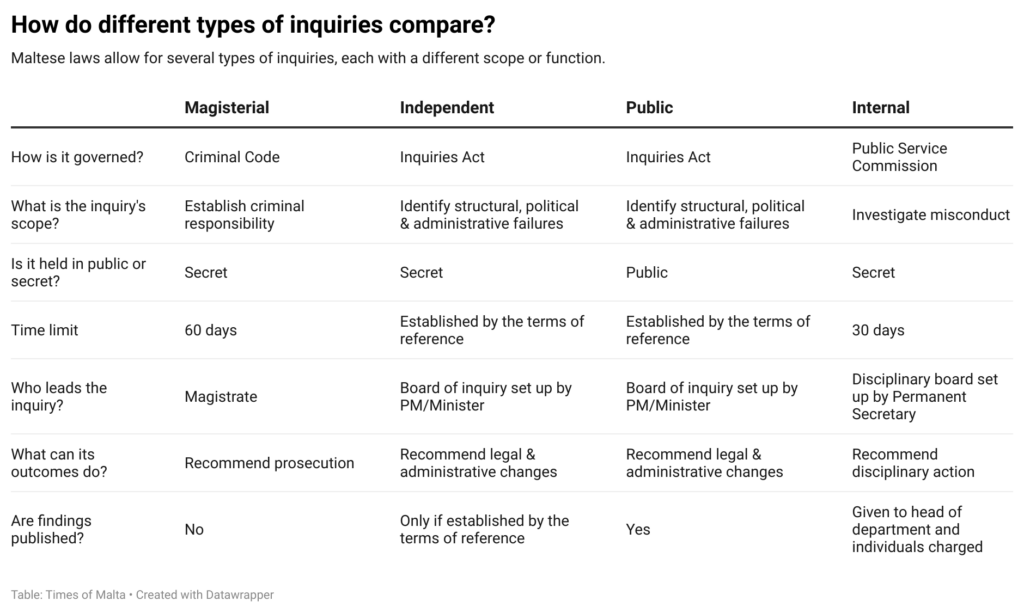

Times of Malta spoke to several legal experts to understand the scope and function of each type of inquiry.

What types of inquiries exist?

Several different inquiries exist, each serving a slightly different purpose, and having different legislative or judicial powers.

Magisterial inquiry

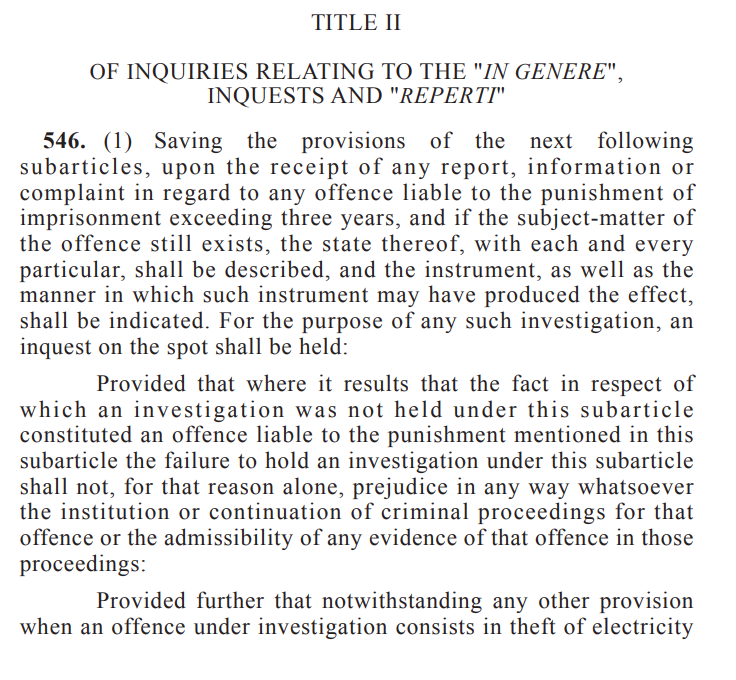

Magisterial inquiries are governed by Malta’s criminal code, with articles 546 to 569 of the code laying out the terms under which such inquiries are held.

The scope of a magisterial inquiry is to establish criminal responsibility and to preserve evidence which may later be used when prosecuting a crime.

The code outlines that a magisterial inquiry may be launched once a request is received either from the police or from a private citizen.

For a magisterial inquiry to be opened, two specific criteria need to be met. Firstly, the potential crime must carry a three-year jail term and secondly, there must be an immediate need for evidence to be preserved.

A magisterial inquiry runs in parallel with the police’s own investigations. Although the two are separate processes, they often work in tandem, with the police working under the guidance of the magistrate.

The magistrate leading the inquiry may appoint all the necessary experts (such as forensic or ballistic experts, for instance), summon witnesses and order searches of property when carrying out their investigation. A witness cannot refuse to appear before an inquiring magistrate.

The inquiry is to be concluded within sixty days, according to the criminal code. If there is a delay, the magistrate must write to the Attorney General to explain the reasons for the delay.

Magisterial inquiries are extremely common. A recent parliamentary question revealed that there are currently 1,698 pending magisterial inquiries, dating as far back as 1979.

The findings of a magisterial inquiry are submitted to the Attorney General, who may send the findings to the police if police action is recommended. The AG may also send the file back to the magistrate asking for further investigation.

Once the inquiry has ended, the people found to be criminally responsible are prosecuted before criminal courts.

Magisterial inquiries are held behind closed doors and their findings are generally not made public, with even the victim’s family often not having access to the inquiry’s conclusions, according to criminal lawyers. However, the AG may choose to publish the conclusions, if they receive a request for this to happen.

Independent inquiry

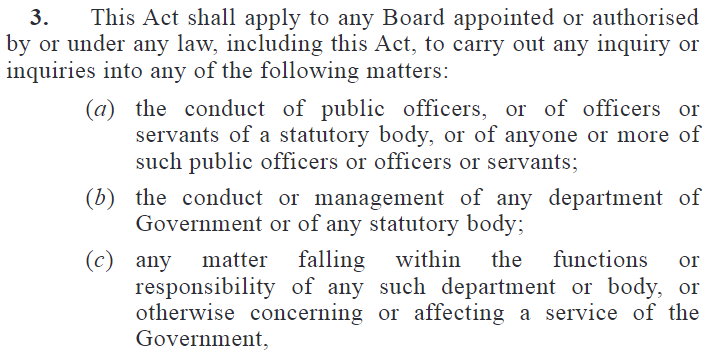

Unlike magisterial inquiries, which fall under the criminal code, independent inquiries are governed by the Inquiries Act, a separate legal tool which sets out how independent inquiries are to be carried out.

An independent inquiry may be initiated by either the Prime Minister or a Minister, who has the power to appoint an inquiry board to investigate possible shortcomings in the conduct of public officers, government bodies or government services.

Independent inquiries are initiated on an ad hoc basis and are political, not criminal, processes. Their limits are set by the terms of reference established by the Minister at the inquiry’s outset. As one legal expert told Times of Malta, “an independent inquiry is ultimately only as good as its terms of reference”.

The goal of an independent inquiry is not to apportion blame or identify culprits. Rather, independent inquiries attempt to identify structural, political and administrative failures, such as maladministration, failures in governance and poor resource allocation.

Accordingly, independent inquiries are limited to recommending or proposing administrative and legal changes but do not have the power to prosecute individuals or directly implement any of their proposed changes.

An independent inquiry may either be held behind closed doors or in the open and its conclusions may either be published or kept confidential. This is established on a case-by-case basis through the terms of reference of each specific inquiry.

Independent inquiries are not infrequent, although relatively few are of public interest.

One recent example is the inquiry into the murder of Bernice Cassar, which found that the state failed Cassar because of a lack of resources and a heavy caseload. In this case, the inquiry was led by retired judge Geoffrey Valenzia and carried out behind closed doors.

In this case the recommendations were made public, not the entire report.

Public inquiry

A public inquiry is simply an independent inquiry that is heard in the open, according to the terms of reference that are set by the prime minister or relevant minister.

All stages of a public inquiry are generally carried out in public, including the testimony of witnesses and the collection of evidence, with the public also able to attend sittings.

Nonetheless, there may be instances where certain testimony may be heard behind closed doors, although this is at the discretion of the inquiry’s board.

Although several high-profile public inquiries have taken place internationally (such as the Chilcot Inquiry investigating the UK’s involvement in the Iraq war), they are rare in Malta, with only two having taken place in its history.

The most recent is the well-documented public inquiry into the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia. The inquiry was launched in 2019 and concluded two years later in 2021, finding that “the state should shoulder responsibility for the assassination”.

The Caruana Galizia inquiry was chaired by a three-person board composed of retired judge Michael Mallia, former chief justice Joseph Said Pullicino and Madam Justice Abigail Lofaro. The board, together with the inquiry’s terms of reference, were established following discussions between the government and the Caruana Galizia family.

An earlier public inquiry took place in February 1996, following allegations made by then-opposition leader Alfred Sant into irregularities in the procurement process of a bus ticketing system. Sant alleged that the company that won the tender, Wayfarer Transit Systems, were sent a copy of the tender document twelve days before it was published and that the tender’s terms were amended in the company’s favour.

A public inquiry was launched by then-Prime Minister Eddie Fenech Adami, who appointed retired judge Victor Caruana Colombo as the sole person on the inquiring board, despite the opposition’s protestations.

The inquiry was initially meant to be concluded within four weeks, however, this was eventually extended and the process was completed by June 1996, lasting a total of five months.

The inquiry found no wrongdoing on the part of then-transport minister Michael Frendo. However, a 1997 review of the case by former AG Edgar Mizzi found that the process was tainted by “a number of irregular facts”, some of which “could amount to serious crimes”, before concluding that “little has been done about them, if anything”.

Internal inquiry

An internal inquiry is primarily a process within the public service’s disciplinary procedures. The terms of internal inquiries are established by the Public Service Commission.

Internal inquiries are generally quicker than other forms of inquiries, starting within thirty days of the alleged offence, triggered by the head of the particular entity or department. The inquiry has a further thirty days to reach its conclusion, although this may be extended by another month in certain instances.

However, the scope of an internal inquiry is somewhat different to that of other inquiries, primarily investigating the conduct of an individual or group of employees, rather than broader administrative, legal or criminal responsibility.

Cases are heard before a disciplinary board of at least three people, appointed by the respective ministry’s permanent secretary.

Internal inquiries are fairly common, although relatively few reach the public spotlight. One recent example was that into seven St Vincent de Paul workers suspected of involvement in the disappearance of resident Carmelo Fino.

What are the key differences between magisterial and public inquiries?

Magisterial and independent (or public) inquiries investigate fundamentally different things and present different conclusions, even when dealing with the same incident.

While a magisterial inquiry seeks to establish criminal responsibility, an independent inquiry tries to identify whether there are failings of the state or of its statutory bodies, even if these failings do not amount to criminal offences.

Independent inquiries do not attempt to pin criminal responsibility upon anyone and are more interested in the legal, administrative and political processes that led to the incident.

Although the findings of a magisterial inquiry may also suggest broader institutional failure, this is secondary to the inquiry’s aims as part of a criminal investigation. Likewise, while the findings of an independent inquiry may also hint at criminal responsibility, it does not explicitly set out to do so.

Furthermore, while a magisterial inquiry investigates a case within the confines of Malta’s current laws, a public inquiry can go one step further and question whether there are shortcomings in the country’s legal, administrative or political structure.

Verdict

Magisterial inquiries attempt to determine criminal responsibility in a case, while public inquiries examine broader systemic and governance issues.

In the case of the death of Jean Paul Sofia, a magisterial inquiry is intended to determine who carries criminal responsibility for the incident, but it is not directly tasked with examining whether administrative or legislative failures were also at play.

On the other hand, a public inquiry would be set up to directly investigate these issues and recommend political and administrative changes, not criminal action.

The claim is therefore false as the evidence clearly refutes it.

The Times of Malta fact-checking service forms part of the Mediterranean Digital Media Observatory (MedDMO) and the European Digital Media Observatory (EDMO), an independent observatory with hubs across all 27 EU member states that is funded by the EU’s Digital Europe programme. Fact-checks are based on our code of principles.

Let us know what you would like us to fact-check, understand our ratings system or see our answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the service.